BUSINESS ESSENTIALS Vol 4, No 12

Dear Esteemed Member,

As you are well aware, Government’s policy thrust in boosting its non-oil exports in response to negative impact of fluctuating oil prices on the Nigerian economy is the “Export Expansion Grant (EEG)”. This is targeted at enhancing efficiency, transparency and accountability in the administration of the key incentive for non-oil export development. We have, therefore devoted ample time to review the relevant guidelines on the intervention circulated by the Nigeria Export Promotion Council (NEPC) for exporters to gain access into the scheme with deadlines.

We also took a cursory look at the recent Government approval in principle of the implementation of Voluntary Assets and Income Declaration Scheme (VAIDS), a means to widening the tax base of the economy. In furtherance of our continued enlightenment series, we shared a useful piece on “Industrial Relations Policy and Good Industrial Relations”, which as well know formed the bedrock of any Human Resources relationships in the workplace.

Our regular Labour and Employment Law Review and Upcoming Training Programmes were not left out.

Have a pleasant reading.

Timothy Olawale

Editor

In this Issue:

- Export Expansion Grant (EEG): Submission of Baseline Data for Export Ratings

- Inflation Figure Drops again in March 2017

- Industrial Relations Policy and Good Industrial Relations

- Widening The Tax Base: Panacea for Improving Contributions To GDP

- Labour & Employment Law: The National Industrial Court

- Upcoming Training Programmes

When You’re Annoyed by a Colleague, Take a Look in the Mirror When You’re Annoyed by a Colleague, Take a Look in the Mirror

Sometimes you work with someone you just don’t like. Maybe your colleague rubs you the wrong way, disagrees with you constantly, or is arrogant and entitled. Before you start pointing fingers, take a look in the mirror. Consider how you might be contributing to the problem, and try to objectively assess what you may have done to escalate the issue. Or ask a trusted colleague for their perspective. The goal is to test your assumptions. You may think it’s all the other person’s fault, but that’s rarely the case. What you’re reacting to may have little to do with the other person, and more to do with your own history. It’s possible that the person reminds you of an obnoxious sibling or an old rival. Or maybe you can be a bit of a control freak, and your frustration comes from being unable to call all the shots. If you can understand what you’re bringing to the situation, you’ll know better how to address it. Adapted from the HBR Guide to Office Politics, by Karen Dillon |

Export Expansion Grant (EEG): Submission of Baseline Data for Export Ratings

The Nigerian Export Promotion Council (NEPC) has released a circular informing all Exporters generally or those already registered for the Export Expansion Grant (EEG) Scheme on available window of opportunity with the lifting of the suspension on the Scheme by the Federal Government. Submissions of 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016 baseline data for the purpose of determining EEG rates for 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017 non-oil exports respectively has been flagged off from Wednesday March 29, 2017.

Documentation Requirements:

- Complete Baseline forms 1A, 1B, 1C and their annexes (the forms can be assessed on www.nepc.gov.ng)

- Audited Financial Statements, which must include Value Added Statements for the respective base years.

Notes:

- Photocopies of Financial Statements are not acceptable. Any photocopy must be duly certified by the Company’s Auditor

- Companies, who are submitting baseline data for the first time should in addition to the above, submit their Financial Statements for 2011, 2012 and 2013, if applicable.

- New companies should submit their current Management Account and Projected Financial Statements for 2018.

In order to ensure that the information provided in the baseline data forms conform with what is contained in the Audited Financial Statement, all exporters are further requested to provide the following additional information:

- Analysis of Turnover into Local and Export Sales

- Analysis/Schedule of Total Export Sales (N) showing the conversion rates used

- Details of Addition to Fixed Assets during the Year.

- Breakdown/Analysis of Cost of Sales into local and Foreign Input (Raw materials and packaging).

All figures must correspond to the information provided in the Audited Financial Statement for the period under review.

In line with the reviewed guidelines, all exporters are expected to include in their submission the company’s 5-year Export Expansion Plan (EPP).

Inflation Figure Drops again in March 2017

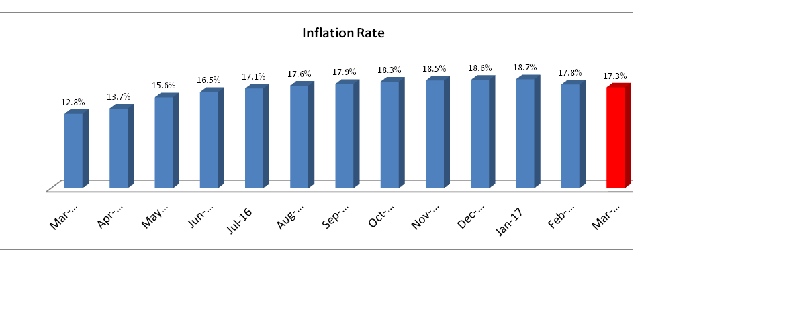

Based on the recently data released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) for March 2017, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) which measures inflation increased by 17.26 percent (year- on-year) albeit at a slower pace, 0.52 percent points lower from the rate recorded in February (17.78) percent.

This would be the second consecutive month that the pace of annual inflation slowed after increasing for fifteen straight months, representing the effects of stabilizing prices in already high food and non-food prices. Currency appreciation in the parallel market witnessed in March (13% month-on-month) also serves to dampen inflationary pressures.

According to the data, the major divisions responsible for accelerating the pace of the increase in the headline index were Housing, Water, Electricity, Gas and Other Fuel, Education, Food and Alcoholic Beverages, Clothing and Footware and Transportation Services.

Implications for Business

Monetary Policy Responses:

- Despite the improving inflation profile, the Central Bank will likely refrain from adjusting its benchmark interest rate immediately. At double digits, inflation is still outside the monetary regulator’s target, thereby limiting the room for further monetary easing.

- With no change in rates expected, the focus will be on the central bank’s guidance and on its stance on liquidity.

Money and Fixed Income Market:

- Yields in the fixed income market are likely to remain elevated in line with still-high inflation rate. This will continue to induce asset reallocation from equities, thereby further encouraging bearish stock market. However, this may over time create entry opportunities in the equities market.

Industrial Relations Policy and Good Industrial Relations

The traditional view of the role of management in industrial relations seems to indicate that policy-level management has usually accorded a low priority to the managing of industrial relations. Some attempts have been made to advance some reasons for this view.

The first is that some management continue to view the prospect of power sharing with trade unions as being a threat not only to their decision-making authority but also to their organisational legitimacy. In this position, trade unionism is still seen as an unwarranted challenge to the right of management to manage.

The second reason is that industrial relations is only part of the overall management function and for those managements which do not regard them as the very essence of their organisational role, they would have considerable difficulty in obtaining total commitment and attention to the managing of industrial relations at board or top management level because board-level and senior managerial appointments will continue to be dominated by other more traditional professional groups.

The third reason is where the policy and practice of industrial relations in a company gives line managers little incentive to be party to day-to-day industrial relations. In other instances, especially where large Human Resource departments have been established, line managers often prefer to delegate their industrial relations role to HR managers rather than to cope with it themselves. This situation is sometime encouraged by HR/IR specialists because it provides added status, power and prestige to their own roles within their employing organisations. Where such an ideology prevails, the outcome is that the state of industrial relations would be chaotic.

It is for these reasons that a number of prescriptions for change have been suggested. One of them is that in order to promote the orderly and effective regulation of industrial relations within companies the boards of companies should review industrial relations within their undertakings. The other is that company boards and senior management should take the initiative in reviewing company industrial relations by the promotion of positive HR policies, by the creation of orderly collective bargaining machinery, and by the formalization of industrial relations procedures. Yet, another prescription is that good industrial relations are the joint responsibility of management and of employees and the trade unions representing them, but the primary responsibility for their promotion rests with management which should take the initiative in creating and developing them. Managers at the highest level therefore, should give, and show that they give, just as much attention to industrial relations as to such functions as finance, marketing, production or administration.

Partly as a result of the restructuring of Nigerian trade unions and the revision of labour legislation, steps have been taken by some management to define their corporate industrial relations policies more clearly than hitherto and to clarify the respective roles of line and HR management.

Two questions might be asked at this stage and an attempt made to answer them, the first is, what is an industrial relations policy? And the second is, what are the essential process elements in the achievement of good industrial relations?

An industrial relations policy is an attempt to define an organisation’s proposed courses of action in its dealings with its employees and their trade unions. As such, it provides a set of guidelines within which management can play a positive part in the conduct of industrial relations. At its optimum, an industrial relations policy covers all aspect of collective bargaining, including trade union recognition. It is also concerned with an organisation’s grievance and disciplinary procedures, its arrangements for joint consultation and its broad range of employment policies which impinge upon industrial relations decision making. These include manpower planning, recruitment and selection, training, payment systems, the status and security of employees and so on. The foregoing list should be regarded as a summary of the key elements of an industrial relations policy. It would, however, be wrong to prescribe a “model” policy since differing organisational demands would inevitably lead to emphasis on certain aspects to the neglect of others.

Producing such a policy is obviously a time consuming process and it clearly requires determination by top management to make it work. But it cannot work successfully without the agreement and acceptance of those subordinate managers who have to implement the policy in question, and of those trade unions and employees most affected by them. For example, although line managers are mainly concerned to see that their employer’s corporate policies are executed and that work targets are achieved in their area of responsibility, industrial relations necessarily forms an important part of their overall responsibilities.

There are thus a number of reasons for having a coherent company industrial relations policy. These may be summarised as follows:

Firstly, it serves as a means of ensuring consistency between operations and different establishments. Secondly, it enables line management to know exactly where it stands in industrial relations in order to remove uncertainty, and it provides guidelines to assist in its activities. Thirdly, if published, it enables employees (other than management) to know the position of their employer on a variety of matters. The growing intervention of the law has increased the necessity for this. Fourthly, it causes management to plan ahead in industrial relations and encourages it to be prospective, proactive and creative in its conduct rather than retrospective, reactive and defensive. Finally, and perhaps most optimistically, it should enable industrial relations objectives to tie in with general business objectives and allow for the importance of industrial relations to be identified as a crucial variable in managing the organisation.

It is interesting to note that the opinions of many practitioners gravitate to the view that even though managements were generally more systematically alive to labour-management relations nowadays, the use made of policies and new machinery is patchy and there is only intermittent evidence that boards of directors have moved far from the traditional view that labour-management relations are a factor to be taken into account only as and when the need arises.

Too much should not, however, be expected from the formulation of policy objectives or from their commitment to paper. For example, the prescription of a set of rules or strategy that is so tight as to cover every eventuality would tend to stifle rather than enhance co-operation between the parties.

But there is a close link between an effective industrial relations policy and the emergence of good industrial relations. By giving line management more ideas about the directions in which its organisation is moving, about objectives in relation to trade unions and their role in general, about sources of information of specialist issues, and about general standards in relation to discipline, health and safety procedures, and productivity, an industrial relations policy can be of considerable benefit. In addition, the fact that the process of discussing the formulation of policy leads management to plan ahead, to consider its current position, and to evaluate strategies for the future can only be beneficial for the development of good industrial relations. By so doing, it can produce a shift from a defensive posture to an active initiating posture. More particularly, it necessitates an end to ‘fire-fighting’ and a move towards fire prevention.

One test of the effectiveness of an industrial relations policy is the extent to which it provides managers who are responsible for the conduct of industrial relations with a framework of general principles that they regard as helpful and within which they are able to act decisively on day-to-day problems. In other words, formality and informality need not be mutually exclusive. Both can operate at different levels of the organisation and fulfil different purposes.

Once top management has defined its industrial relations policies, it is then incumbent upon it to integrate them into company policy generally, to monitor their operation and to systematically review and adapt these policies in the light of changing circumstances. Indeed, it has been argued that a well defined policy promotes consistency in management and enables all employees and their representatives to know where they stand in relation to the company’s intentions and objectives. It further encourages the orderly and equitable conduct of industrial relations by enabling management to plan ahead, to anticipate events, and to ensure and retain an initiative in changing situations.

The nature of HR manager’s role in industrial relations is, nevertheless, the subject of continuous debate. Some HR specialists see it essentially as an advisory role to line management. They argue that it is the line manager who is responsible for executive action on industrial relations. Others view the HR role as an executive function. They suggest that executive authority for industrial relations requires to be given to a senior member of management with the authority to instruct line managers on the appropriate action to be taken on particular issues. But in practice, the distinction between the advisory and the executive functions of HR is necessarily blurred. For experience suggests that not only that the HR specialist’s basic role is to make line managers more effective in the handling of industrial relations without diminishing their authority, but also that both HR and line manager require the necessary authority to carry out their respective roles in this field. Such an approach necessitates, for example, that the respective roles of the line manager and HR specialist are clarified where possible and, if there is conflict between them, that a means exist by which such conflict can be resolved.

‘Good’ industrial relations to which reference has been made in this article should not necessarily be equated with an absence of conflict nor should it be taken to imply a willingness always to agree with the trade unions or workers’ representatives. For management’s part, good industrial relations is inevitably tied with prior planning, full recognition of the part that trade unions can play in management, and a willingness to consult and negotiate, though not necessarily to agree, on substantive issues. If these factors help to promote successful, efficient and productive companies, then they are worthy objectives in their own right.

There are, however, three essential process elements in the achievement of good industrial relations. These are the concepts of centralisation of power and authority, normative consensus and thrust.

Culled from NECA’s archives

Widening the Tax Base: Panacea for Improving Contributions to GDP

The National Executive Council [NEC] recently approved in principle, the implementation of a Voluntary Assets and Income Declaration Scheme (VAIDS). The Scheme is expected to come into effect from May 2017 once formal guidelines have been issued. The Scheme encourages voluntary disclosure of previously undisclosed assets and income for the purpose of payment of all outstanding tax liabilities. The Scheme will offer a limited waiver for declaration within the specified period of time.

The Scheme is expected to help expand Nigeria’s tax base and therefore improve the low tax to Gross Domestic Product [GDP] ratio currently about 6%. It also seeks to curb the use of tax havens for illicit fund flow and tax avoidance.

It is estimated that the Scheme would generate approximately USD1 billion in tax revenues. Some of the objectives of the Scheme include:

- Increasing Nigeria’s tax to GDP ratio from 6% to 15% by 2020.

- Broadening the Federal and State tax brackets. Only 214 individuals nationwide pay N20 million or more in tax annually.

- Curbing non-compliance with existing tax laws and discouraging use of tax havens.

- Discouraging illicit financial flows and tax evasion.

Highlights of the Scheme

- The Scheme would grant some waivers as a reward for voluntary declaration of assets and payment of tax liabilities.

- All individuals resident in Nigeria and companies operating in Nigeria. However, the primary targets are multinational enterprises and high net worth individuals.

- The disclosure requirements would be in respect of all taxes payable to all levels of government – federal, state and local government taxes including Companies Income Tax, Personal Income Tax, Petroleum Profits Tax, Capital Gains Tax, Stamp Duties, Tertiary Education Tax and Technology Tax.

- Any taxpayer who fails to embrace the voluntary disclosure Scheme will be investigated and if found culpable will be prosecuted in addition to full payment of tax due including penalty and interest.

OPINION

- The Scheme aims to address tax evasion and illicit financial flows particularly by individuals. Given that there are no formal guidelines yet, the details of the limited waiver are not yet known. The Scheme is in line with global best practices on disclosure of information and declaration of assets.

- A similar scheme was adopted in India which resulted in the addition of over 350,000 individuals to the tax net yielding approximately US$1.2 billion.

- There will be collaboration with foreign governments where assets and illicit funds are likely to be held by Nigerians. Government will leverage on various international agreements including the recently ratified Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters which has been signed by over 100 countries.

Labour & Employment Law: Advancing the Frontiers of Employment Law and Practice in Nigeria through Law Reporting: Nigerian Labour Law Reports as a Case Study

The talk of advancing the frontiers of Employment Law and Practice in Nigeria suggests that there are issues with or a void in this area of the law which law reporting will tackle or cover. However, in restricting the discourse to Employment Law, is it that we are conscious of the Employment/Labour Law debate? The point is that today scholars are questioning not just what the boundaries of labour law are, but what is labour law itself? D’Antona , for instance, talks of the ‘identity crisis of labour law’ and gives the example of France where manuals have abandoned the traditional title ‘labour law [droit du travail]’ in preference for ‘the law of employment [droit de l’emploi]’, in order to underlie that the epicenter has moved from labour relations inside the firm or organization to the labour market generally, with its new problems of market access, job creation, sharing of labour time, ‘employability’, and connections between working conditions and social citizenship. In this sense, the problem becomes self-evident in that the labour with which labour law has until now been concerned seems to be found less and less and, where it is found, exhibits characteristics not readily reconciled with the traditional model.

I and no less a personality than our erudite Professor of Labour Law, Professor Chioma Kanu Agomo of the Law Faculty of University of Lagos have over time recognized that labour law is in crisis. Like I indicated, the talk today is mainly about the identity crisis of labour law and the extravagant individualism of the common law. There is the debate as to the choice between individuation of labour rights (employment law) or their collectivization (labour law). The crisis of labour law is succinctly depicted by Sandra Fredman who couched the challenges of labour law in terms of conceptions of the notion of worker, the melting boundary between employment and unemployment with job insecurity elevated into a market asset, the threat posed by globalization in undercutting basic social rights yielding to the necessity to counterbalance the hegemony of free trade ideology, the growing inability of trade unions to cater for those out of work or even marginal workers, etc. All of this points to the importance of ensuring that labour law is facilitative of collective bargaining and social dialogue, rather than simply providing for individual rights.

A quiet revolution regarding labour jurisprudence in the country is currently going on at the National Industrial Court of Nigeria (NIC) since the promulgation of the Third Alteration to the 1999 Constitution, which repositioned the Court within the structure of the Judiciary and as one of the superior courts of record under section 6 of the Constitution with defined and exclusive jurisdiction under especially section 254C of the Constitution, as amended. And this quiet revolution in labour jurisprudence, I dare say, is coming at the heels of the crisis of labour that plagues the world today. The crisis of labour law coming in terms of its identity calls for a re-conceptualisation and reformulation of its boundaries. I had in previous write-ups noted the need to review and reform labour law in Nigeria.

I indicated that since the Third Alteration to the 1999 Constitution, a quiet revolution regarding labour jurisprudence in the country is currently going on at the NIC. Professor Agomo in her book actually talks of the increasing visibility of the NIC in the development of labour law jurisprudence. A few instances typifying the point I seek to make will suffice.

- The recognition by the NIC that irrespective of the employer’s right to hire and fire for any or no reason, it is no longer globally fashionable in industrial relations law and practice to terminate an employment relationship without adducing any valid reason for such a termination. See Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN) v. Schlumberger Anadrill Nigeria Limited .

- The recognition by the NIC that the banking sector is sensitive for which termination with immediate effect suggests some wrongdoing and which the employer must justify if he is not to be saddled with more than one month’s pay in lieu of notice. See Andrew Monye v. Ecobank Nigeria Plc .

- The current absence of legal rules regulating atypical work, the signposts shown by the NIC regarding the vexed issue of outsourcing and contracting out, and how a successful action can be maintained by aggrieved employees. See PENGASSAN v. Mobil Producing Nigeria Unlimited.

- The affirmation by His Lordship Hon. Justice B. A. Adejumo, PNICN that termination on the ground of pregnancy will attract the award of heavy damages. See Mrs. Folarin Oreka Maiya v. The Incorporated Trustees of Clinton Health Access initiative, Nigeria & 2 ors , where compensation to the tune of five Million, Five Hundred and Seventy-Six Thousand, Six Hundred and Seventy Naira (N5,576,670.00) being one year’s full gross pay was awarded. The applicant did not ask for reinstatement; and so this was not considered or granted.

- The first successful award for sexual harassment in the workplace by Her Ladyship Hon. Justice O. A. Obaseki-Osaghae in Ejieke Maduka v. Microsoft Nigeria Limited & ors .

- The acknowledgment of the special nature of the NIC as an industrial court and the fact of the superior bargaining power of employers over employees. See Mr. Kurt Severinsen v. Emerging Markets Telecommunication Services Limited.

- The clarification of the relationship between section 12 and section 254C(1)(f), (h) and (2) of the 1999 Constitution, as amended, regarding application of international conventions and international best practice in terms of the jurisdiction of the NIC. See Aero Contractors Co. of Nigeria Limited v. National Association of Aircrafts Pilots and Engineers (NAAPE) & ors .

- The clarification of the concept of notional promotion in terms of the 8-year tenure policy for Directors in the Public Service. See Ambassador D. C. B. Nwanna v. National Intelligence Agency & ors .

- The clarification that trade unions, without more, are not the policemen of labour practices in the world of work. See Errand Express Ltd v. Maritime Workers Union of Nigeria .

- Acknowledgment and application of the concept constructive dismissal in the corpus of labour jurisprudence in Nigeria. See Mr. Patrick Obiora Modilim v. United Bank for Africa Plc .

- Acknowledgment that expectation interest in deserving cases may be recoverable by an employee against his employer. See Medical and Health Workers Union of Nigeria & ors v. Federal Ministry of Health and Mr. Patrick Obiora Modilim v. United Bank for Africa Plc .

How can lawyers, academics, students and even judges get to find out these new grounds that are being broken daily in the field of labour jurisprudence? This is where the NLLR comes in to fill the void.

But even at this, the NIC, of course, suffers the indignation of the label of being a Court at large, making new law and going against the established orthodoxy/norms with little or no appellate supervision . But solace the NIC must take in the words of Lord Edmund-Davis. Chief Bolaji Ayorinde SAN in a write-up had quoted Lord Edmund-Davis who, in his book Judicial Activism 1975, wrote as follows –

Whatever a judge does, he will most surely have his critics. If, in an effort to do justice, he appears to make new law, there will be cries that he is overweening and that he has rendered uncertain what had long been regarded as established legal principles. On the other hand, if he sticks to the old legal rules, an equally vocal body will charge him with being reactionary, a slave to precedent, and of failing to the mould the law to changing social needs. He cannot win, and, if he is wise, he will not worry, even though at times he ruefully reflect that those who should know better seem to have little appreciation of the difficulties of his vocation. He will just direct himself to the task of doing justice in each case as it comes along. No task could be nobler.

It is when the Court breaks new ground(s) in terms of the ratio of its decisions, issues such as items 1 – 10 enumerated above, that law reporting is meant to bring to the fore, and which the NLLR currently does bring to the fore. The ensuing discussion is an attempt at providing the justification for this. To Chief Bolaji Ayorinde SAN, it was WTS Daniel QC in 1863 who proposed the Council of law Reporting and then suggested what a good Law Report should include and what ought to be excluded. It was clear to him and as it should be clear to all that cases which were valueless as precedents and those which were substantially repetitions of what was reported already ought to be excluded. In this wise, a good Law Report must necessarily include –

- All cases which introduce, or appear to introduce, a new principle or a new rule,

- All cases which materially modify an existing principle or rule,

- All cases which settle, or materially tend to settle, a question upon which the law is doubtful, and

- All cases which for any reason are peculiarly instructive.

Hon Justice Steven Rares, Chair of the Consultative Council of Australian Law Reporting, in his introductory remarks at the Future of Law Reporting in Australia Forum, which held in Brisbane on 2nd August 2012 , reiterated these requirements of good law reporting but asserted that any of the requirements or all of them would be sufficient to ground a Law Report.

In addition, the Law Report must be accurate, contain everything material and useful and be concise. In particular, they should show the parties, the nature of the pleadings, the essential facts, the points contended and the grounds on which the judgment was based as well as the judgment, decree or order actually pronounced. Measured against these indices, the NLLR over the years has fared very well, give and take the now and then (occasional) errors one finds in it. I have had occasions to call on our guest of honour on some of these errors, which by and large are often the work of the printer’s devil.

If one takes a look at the NLLR, one will notice that it contains the subject matter arising from every case reported, the issues arising, facts of the case and ratio or reasons for the decision which all come before cases and statutes referred to in the report and finally the full report of the case. It also contains an index of cases reported, index of subject matter, index of cases (Nigerian and foreign) referred to, index of statutes referred to, index of Rules of Court referred to and index of books referred to in the Report.

The common law is hinged on the doctrine of judicial precedent based on stare decisis. By this doctrine, decisions of superior courts of record are binding; and binding according to whether they emanate from one superior court over the other. In other words, while decisions of courts of coordinate jurisdiction remain persuasive amongst themselves, the decisions of higher courts are binding on all lower courts. This being the case, it is absolutely necessary for these decisions of the superior courts to be available to all so that what they decide as the law would become known. This is where the law Reports come in – to make known as law decisions of the superior courts. However, the practice in Nigeria is that the decisions of the appellate Courts enjoy more attention of the Law Reports than courts of first instance. The reason for this is not farfetched. Since most cases are contentious and so have a tendency not to end at the court of first instance, invariably they end on appeal to the Court of Appeal and then ultimately the Supreme Court. It is accordingly the decision of the Appellate Courts that become judicial precedent. So when the NLLR concentrates on labour law decisions, it becomes understandable given that this is one area where appeals from the decisions of the NIC is very limited. In any case, it must be noted that an unbridled right of appeal over employment matters right up to the Supreme Court has actually been frowned on even by the Supreme Court itself as is the case in Osisanya v. Afribank Plc and Ifeta v. Shell Petroleum Development Company Limited .

The NLLR has been on our book shelves since 2004 when the first Part was published. The sad thing, and this is what I see on a day to day basis when adjudicating labour disputes, is that the rate at which counsel refer to the cases cited in the NLLR is very minimal. I have had heard arguments from counsel regarding for instance section 7 of the NIC Act 2006 on the ambit of the NIC’s jurisdiction over issues relating to ‘labour’. The disturbing fact is that even when the NIC had made pronouncement on what the word ‘labour’ means for purposes of its jurisdiction, counsel chose not to even refer to such a decision, preferably relying on “Supreme Court and Court of Appeal” cases even when these latter cases bear no relevance or relationship to the issue before the NIC. I have, for instance, in the oral argument of the defence counsel in Mr. Omu Henry Akamovba v. Nigerian Security Printing & Minting Co. Plc heard that in the hierarchy of laws Supreme Court decisions take priority over statutory enactments. When I pointed out that this can only when the Supreme Court brands the statutory enactment unconstitutional, the counsel to the defendant vehemently argued otherwise. I was left at a loss the kind of legal education counsel possessed since one of the very first things thought to law students in the course, Nigerian Legal System, is that in the hierarchy of laws the Constitution (a statutory enactment) comes first followed by other statutory enactments (Acts of the National Assembly and Laws of State Houses of Assembly), case law (Supreme Court decisions, Court of Appeal decisions, decisions of High Courts, etc in that order) and then customary law, all in the order presented.

The point I simply wish to make is that the utilization of the NLLR by lawyers has been generally less than satisfactory especially for a Court like the NIC whose decisions are subject to a minimal right of appeal. Despite the caution of the Supreme Court in Osisanya v. Afribank Plc and Ifeta v. Shell Petroleum Development Company Limited, the fixation with Supreme Court and Court of Appeal decisions by lawyers, good as it may be, must not be an absolute disposition. The NLLR must on that score alone command a peculiar mass appeal to especially labour lawyers as the NLLR remains the market leader when it come to labour law practice. To my mind, any labour lawyer that overlooks the NLLR simply does that at his or peril. Like it is often said, a word is enough for the wise.

A paper presented by Hon. Justice Benedict Bakwaph KANYIP, PhD, Presiding Judge, National Industrial Court, Lagos Division

APR 28 Nigerian Labour Law When: Happening Now !!! |

MAY 10 Planning for Golden Years When: May 10-12, 2017 |

MAY 25 Exceptional Customer Care When: May 24-25, 2017 |

For further details please contact Adewale (08069720364) adewale@neca.org.ng

Visit www.neca.org.ng

Recent Comments