BUSINESS ESSENTIALS Vol. 3 No 24

Dear Esteemed Member,

We continued our analysis of the 2016-2017 Global Competitiveness Report with a focus on basic requirements / determinants of how countries, especially Nigeria fared based on macroeconomic environments and other factors. We also highlighted key features of the recently released National Code of Corporate Governance for Private Sector from Financial Reporting Council of Nigeria.

Our regulars were not left out.

Have a pleasant reading.

Timothy Olawale

Editor

In this Issue:

- Global Competitiveness Index: How Nigeria Fared Under The Basic Requirements Sub index

- Financial Reporting Council Of Nigeria’s National Code Of Corporate Governance 2016 For The Private Sector- Key Highlights

- LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT LAW: Collective Agreement (Ganiu Lawal & 3 others vs. Federated Steel Mills Limited, 2014) 42 N.L.L.R. Pt 130, P. 306 NIC

- Upcoming Training Programmes

GLOBAL COMPETITVENESS INDEX: HOW NIGERIA FARED UNDER THE BASIC REQUIREMENTS SUBINDEX

Nigeria is among African economies hardest hit by the reduction in commodity prices, falling three places to 127th overall almost entirely due to its weaker macroeconomic environment (down 27 places) and financial sector (down 10 places). Although still relatively low, the government deficit has almost doubled since last year and national savings has significantly suffered, worsening the current account position. Banks are less solid, reducing the availability of credit, despite the Central Bank ending its currency peg, financial authorities have retained restrictions on access to the interbank market, meaning access to finance will remain difficult for many businesses.

Additional factors holding back Nigeria’s competitiveness include an underdeveloped infrastructure (132nd), which is again rated as the country’s most problematic factor for doing business; insufficient health and primary education (138th), with only 63 percent of children enrolled in primary school; and the poor quality and quantity of higher education and training (125th).

The Global Competitiveness Report 2016- 2017 defines competitiveness as the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country. The level of productivity, in turn, sets the level of prosperity that can be reached by an economy. The productivity level also determines the rates of return obtained by investments in an economy, which in turn are the fundamental drivers of its growth rates. In other words, a more competitive economy is one that is likely to grow faster over time. This open-endedness is captured within the Global Competiveness Index (GCI) by including a weighted average of many different components, each measuring a different aspect of competitiveness. The components are grouped into 12 categories, the pillars of competitiveness. As mentioned in our last publication, we will analyse in parts the 12 Pillars, starting with the first four pillars:

1st pillar: Institutions

Under this subhead, the institutional environment of a country depends on the efficiency and the behaviour of both public and private stakeholders. The legal and administrative framework within which individuals, firms, and governments interact determines the quality of the public institutions of a country and has a strong bearing on competitiveness and growth. It influences investment decisions and the organization of production and plays a key role in the ways in which societies distribute the benefits and bear the costs of development strategies and policies. Good private institutions are also important for the sound and sustainable development of an economy. The 2007–08 global financial crisis, along with numerous corporate scandals, has highlighted the relevance of accounting and reporting standards and transparency for preventing fraud and mismanagement, ensuring good governance, and maintaining investor and consumer confidence.

2nd pillar: Infrastructure

Extensive and efficient infrastructure is critical for ensuring the effective functioning of the economy. Effective modes of transport—including high-quality roads, railroads, ports, and air transport—enable entrepreneurs to get their goods and services to market in a secure and timely manner and facilitate the movement of workers to the most suitable jobs. Economies also depend on electricity supplies that are free from interruptions and shortages so that businesses and factories can work unimpeded. Finally, a solid and extensive telecommunications network allows for a rapid and free flow of information, which increases overall economic efficiency by helping to ensure that businesses can communicate and decisions are made by economic actors taking into account all available relevant information.

3rd pillar: Macroeconomic environment

The stability of the macroeconomic environment is important for business and, therefore, is significant for the overall competitiveness of a country. Although it is certainly true that macroeconomic stability alone cannot increase the productivity of a nation, it is also recognized that macroeconomic disarray harms the economy, as we have seen in recent years, conspicuously in the European context. The government cannot provide services efficiently if it has to make high-interest payments on its past debts. Running fiscal deficits limits the government’s future ability to react to business cycles. Firms cannot operate efficiently when inflation rates are out of hand. In sum, the economy cannot grow in a sustainable manner unless the macro environment is stable.

4th pillar: Health and primary education

A healthy workforce is vital to a country’s competitiveness and productivity. Workers who are ill cannot function to their potential and will be less productive. Poor health leads to significant costs to business, as sick workers are often absent or operate at lower levels of efficiency. Investment in the provision of health services is thus critical for clear economic, as well as moral, considerations. In addition to health, this pillar takes into account the quantity and quality of the basic education received by the population, which is increasingly important in today’s economy. Basic education increases the efficiency of each individual worker.

| Rank/138 | Value | Rank/138 | Value | |||||

| 1st Pillar: Institutions | 118 | 3.3 | 2nd Pillar: Infrastructure | 132 | 2.1 | |||

| 1.01 | Property rights | 95 | 4 | 2.01 | Quality of overall infrastructure | 132 | 2.1 | |

| 1.02 | Intellectual property protection | 112 | 3.4 | 2.02 | Quality of Roads | 126 | 2.6 | |

| 1.03 | Diversion of public funds | 127 | 2.2 | 2.03 | Quality of railroad infrastructure | 103 | 1.5 | |

| 1.04 | Public Trust in Politicians | 131 | 1.7 | 2.04 | Quality of port infrastructure | 117 | 2.8 | |

| 1.05 | Irregular payments and bribes | 129 | 2.6 | 2.05 | Quality of air transport infrastructure | 119 | 3.2 | |

| 1.06 | Judicial Independence | 76 | 3.8 | 2.06 | Available airline seat kilometres (million/week) | 55 | 318 | |

| 1.07 | Favouritism in decision of government officials | 127 | 2.6 | 2.07 | Quality of electricity supply | 137 | 1.4 | |

| 1.08 | Wastefulness of government spending | 126 | 2.2 | 2.08 | Mobile-cellular telephone subscriptions | 118 | 82.2 | |

| 1.09 | Burden of government regulation | 107 | 3.0 | 2.09 | Fixed-telephone lines/100 pop. | 137 | 0.1 | |

| 1.10 | Efficiency of Legal framework in settling disputes | 86 | 3.3 | |||||

| 1.11 | Efficiency of Legal framework in challenging regulations | 85 | 3.2 | 3rd Pillar: Macroeconomics | Rank/138 | Value | ||

| 1.12 | Transparency of Government policymaking | 113 | 3.5 | 108 | 4.0 | |||

| 1.13 | Business costs of terrorism | 132 | 3.0 | 3.01 | Government budget balance (% GDP) | 86 | -4.0 | |

| 1.14 | Business costs of crime and violence | 121 | 3.0 | 3.02 | Gross National savings (% of GDP) | 116 | 12.0 | |

| 1.15 | Organised crime | 110 | 4.0 | 3.03 | Inflation (annual % change) | 125 | 9.0 | |

| 1.16 | Reliability of police services | 121 | 3.0 | 3.04 | Government debt (% GDP) | 7 | 11.5 | |

| 1.17 | Ethical behaviour of firms | 117 | 3.2 | 3.05 | Country credit rating ( 0-100) best | 88 | – | |

| 1.18 | Strength of auditing and reporting standards | 56 | 4.9 | |||||

| 1.19 | Efficacy of corporate boards | 49 | 5.1 | Rank/138 | Value | |||

| 1.20 | Protection of minority shareholders’ interests | 50 | 4.2 | 4th Pillar: Health and Primary education | 138 | 2.8 | ||

| 1.21 | Strength of investor protection | 20 | 6.8 | 4.01 | Malaria incidence cases/100,000 pop. | 64 | 33243.9 | |

| 4.02 | Business impact of malaria | 58 | 3.6 | |||||

| 4.03 | Tuberculosis incidence cases/100,000 pop. | 127 | 322.0 | |||||

| 4.04 | Business impact of tuberculosis | 91 | 5.0 | |||||

| 4.05 | HIV prevalence % adult pop. | 123 | 3.2 | |||||

| 4.06 | Business impact of HIV/AIDS | 105 | 4.5 | |||||

| 4.07 | Infant mortality (death/1,000 live births) | 134 | 69.4 | |||||

| 4.08 | Life expectancy years | 134 | 52.8 | |||||

| 4.09 | Quality of primary education | 124 | 2.8 | |||||

| 4.10 | Primary education enrolment rate (net %) | 136 | 63.8 |

Classification by each stage of development: Nigeria is just transiting from factor-driven economy to efficiency-driven… still in the hood

| Stage 1: factor-driven

(35 economies) |

Transition from stage 1 to stage 2

(17 economies) |

Stage 2: Efficiency-driven

(30 economies) |

Transition from stage 2 to stage 3

(19 economies) |

Stage 3: Innovation-driven

(37 economies) |

|||

| Bangladesh | Malawi | Algeria | Albania | Iran | Argentina | Australia | Korea republic |

| Benin | Mali | Azerbaijan | Armenia | Jamaica | Barbados | Austria | Luxembourg |

| Burundi | Mauritania | Bhutan | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Jordon | Chile | Bahrain | Malta |

| Cambodia | Moldova | Bolivia | Brazil | Macedonia | Costa Rica | Belgium | Netherlands |

| Cameroon | Mozambique | Botswana | Bulgaria | Montenegro | Croatia | Canada | New Zealand |

| Chad | Nepal | Brunei Darussalam | Cape Verde | Morocco | Hungary | Cyprus | Norway |

| Congo, democratic rep. | Nicaragua | Gabon | China | Namibia | Latvia | Czech republic | Portugal |

| Cote d’ivoire | Pakistan | Honduras | Colombia | Paraguay | Lebanon | Denmark | Qatar |

| Ethiopia | Rwanda | Kazakhstan | Dominican Republic | Peru | Lithuania | Estonia | Singapore |

| Gambia | Senegal | Kuwait | Ecuador | Romania | Malaysia | Finland | Slovenia |

| Ghana | Sierra Leone | Mongolia | Egypt | Serbia | Mauritius | France | Spain |

| India | Tajikistan | Nigeria | El Salvador | South Africa | Mexico | Germany | Sweden |

| Kenya | Tanzania | Philippines | Georgia | Thailand | Oman | Greece | Switzerland |

| Kyrgyz Republic | Uganda | Russian Federation | Guatemala | Tunisia | Panama | Hong Kong | Taiwan |

| Lao PDR | Yemen | Ukraine | Indonesia | Poland | Iceland | Trinidad and Tobago | |

| Lesotho | Zambia | Venezuela | Saudi Arabia | Ireland | United Arab emirates | ||

| Liberia | Zimbabwe | Vietnam | Slovak Republic | Israel | United kingdom | ||

| Madagascar | Turkey | Italy | United States | ||||

| Uruguay | Japan | ||||||

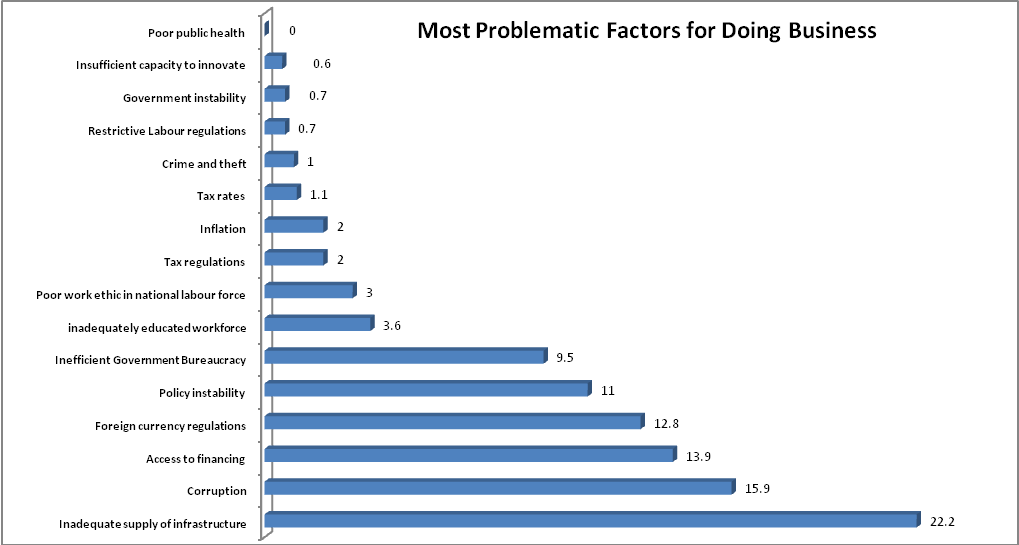

Factors identified as most problematic for doing business in Nigeria

Respondents to the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey were asked to select the five most problematic factors for doing business in their country and to rank them between 1 (most problematic) and 5. The score corresponds to the responses weighted according to their rankings.

Source: World Economic Forum, Executive Opinion Survey, 2016/NECA Research

Source: World Economic Forum, Executive Opinion Survey, 2016/NECA Research

OPINION:

It is high time that the country address some of the factors identified as limitations to Global Competitiveness and attraction of foreign investors. Some of which are:

- Quality of Electricity supply (137th out of 138)

- Primary education enrolment rate ( 136th )

- Business costs of terrorism (132nd)

- Quality of overall infrastructure (132nd)

- Public Trust in Politicians (131st )

- Irregular payments and bribes (129th)

- Diversion of public funds ( 127th)

- Favouritism in decision of government officials (127th)

- Wastefulness of government spending (126th)

- Inflation (125th)

FINANCIAL REPORTING COUNCIL OF NIGERIA’S NATIONAL CODE OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 2016 FOR THE PRIVATE SECTOR: KEY HIGHLIGHTS

The Financial Reporting Council of Nigeria (FRCN) released its National Code of Corporate Governance 2016 for the Private Sector (the Code) on 17 October 2016. The Code is applicable to (x) public companies (both listed and not listed); (y) private companies that are holding companies or subsidiaries of public companies; and (z) regulated private companies.

Since it’s unveiling, the Code has generated lots of interest to professionals and stakeholders across various sectors. This, amongst other reasons, is due to the fact that the Code by its provisions: (x) seeks to supersede other corporate governance codes which regulate other sectors; (y) provides a “one-size-fits all” code; and (z) is mandatory in its application. Further, some of the provisions of the Code, whilst being unusual, are clearly inconsistent and seek to amend the provisions of the Companies and Allied Matters Act (CAMA) and other statutory legislations. In the paragraphs below, we seek to analyze the legality of the FRCN issuing the Code and highlight certain key provisions of the Code.

LEGALITY OF THE FRCN ISSUING THE CODE

From a read of section 7 and 8 of the Financial Reporting Council of Nigeria Act (FRCN Act) which provides for the powers and functions of the FRCN, it is clear that the intendment of the draftsman was to regulate and enforce accounting, auditing, and financial reporting standards in Nigeria. With this in mind, a further read of section 51(c) of the FRCN Act shows that the Act provides for the powers of the Directorate/Committee on Corporate Governance to issue codes of corporate governance and guidelines. The foregoing reveals an internal disharmony and inconsistencies within the FRCN Act, and more importantly, the FRCN overreached its powers in section 51(c) and 77 of the FRCN Act by issuing a Code which seeks to cover the entire spectrum of corporate governance in Nigeria without limiting itself to regulating the accounting and financial reporting standards of companies.

It is unequivocal that as a subsidiary legislation, the Code cannot by its provisions overreach, override, amend or repeal other existing statutes which have been made by legislative enactment, neither can it amend other subsidiary legislation issued pursuant to already existing Acts of the National Assembly. Such a subsidiary legislation stands the risk of being declared ultra vires the FRCN and being declared null and void, to the extent of its inconsistencies with existing statutes of the National Assembly. Moreso, as it is trite law that where there are two legislations, the legislation which is sector specific would override the more general legislation.

MANDATORY NATURE OF THE CODE

Section 2.3 of the Code provides that the Code is mandatory and this is reinforced by Section 37.1 of the Code which provides that violations of its provisions will occasion personal sanctions and sanctions against the company or firm involved in such violations.

NUMBER OF DIRECTORS

The minimum number of members of the board of directors is eight (8) directors in a public or private company. However, a regulated private company must have not less than five (5) directors. This is a direct contrast to CAMA which provides that all companies must have at least two (2) directors. The effect of this is that companies to which the Code applies will have to take measures to adjust their board structure and composition.

FAMILY MEMBERS

Closely tied to the above, is the issue of family members on the board. According to the Code, not more than two members of the same or extended family can be on the board of one company at the same time. The Code defines an extended family member to mean those persons who may be reasonably expected to influence, or be influenced by, that person in his dealing with a company.

In this instance, companies’ especially private companies which hitherto did not have this sort of restriction would need to adjust their board composition in compliance with the Code.

VOTING POWERS

In relation to the voting powers of directors, the Code provides that where a majority of independent directors do not agree with a decision of the board of directors, such a decision would only stand if it was supported by at least 75 percent of the entire board. The effect of this provision is that it elevates the independent directors above the majority of the board of directors and seems to create an illusion of a two-tier board system in which the executive directors report to the independent (non-executive) directors.

It also contravenes the provisions of CAMA which provide that decisions of the board of directors are arrived at by a majority of votes, and to this end, every director on the board of directors is entitled to one vote.

BOARD APPOINTMENT

The board has the power to develop a written, formal and transparent procedure for board appointment. This document will provide for the criteria for board appointment with emphasis on the strengths and weaknesses of the existing board, required skills and experience, gender and age diversity.

The Code also provides that appointments shall be a matter for the board as a whole. This is in direct conflict with the provisions of CAMA which provides that members at an annual general meeting (AGM) have the powers to appoint directors. The only power directors have to appoint other directors is to fill a casual vacancy caused by retirement, death, resignation or removal. Such an appointment stands subject to the approval of members at the next AGM.

PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

The board has a duty to create an evaluation system which shall include the criteria and key performance indicators and targets for the board, its committees, the chairman and individual committee directors. The board may engage the services of external consultants to facilitate the performance evaluation at least once every three years.

The result of the performance evaluation of each director shall be disclosed in the annual report on a named basis as well as the name of the external consultant facilitating the performance evaluation.

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE EVALUATION

Every company is mandated to undertake an annual corporate governance evaluation which should be facilitated by an independent consultant. The independent consultant must be registered by the regulator for such purpose.

MANAGING DIRECTOR/CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

Under the Code, the Managing Director/Chief Executive Officer (MD/CEO) cannot go on to become the chairman of the same company. However, should the Board decide that a former MD/CEO should become chairman of the company; there must be a seven (7) year cooling period. Furthermore, the board must (x) consult with majority and minority shareholders in advance; (y) inform the regulators disclosing reasons for such appointment; and (z) disclose the reason in the next annual report.

MINORITY INTEREST EXPROPRIATION

To protect minority shareholders and other external stakeholders, the Code precludes insiders from engaging in transfers of assets and profits out of company for their personal benefits or for the benefit of those who directly or indirectly control the company.

Minority shareholders who individually or as a group hold not less than one percent of the share capital in a company are also entitled to submit items for inclusion in the agenda of the AGM of the company. This is cumbersome and would create a number of administrative hurdles for the company.

Most importantly, controlling shareholders have fiduciary duties to minority shareholders and must call a general meeting to discuss major or extraordinary transactions that may materially impact on the business of the company.

OPINION

These are early days and we envisage that diverse issues would be thrown up in the course of implementation. We think it noteworthy to point out that the implementation of the Code, as they were not birthed by any legislative process in the National Assembly may be faced with major hurdles, given the inconsistency with quite a few of its provision, with substantive law.

Without more, the Code in its present form, cannot operate to amend or repeal either FRCN Act [80] or any other legislative enactment; and where any provisions of the Code is inconsistent with the FRCN Act and/or any extant Nigerian Law, same stands the risk of being declared null and void, to the extent of their inconsistency, by a law court, at the instance of any interested party.

Thus, certain provisions of the Code, which are inconsistent with extant legislation on relevant issues, may be difficult to enforce, or cause further regulatory overlap, which the unification and harmonisation of the existing codes have sought to end.

Finally, since the Code is expected to help build culture of probity and accountability in the management of business organizations; to prevent organized fraud, corruption of all shades and corporate failures, we hold the considered view that where the Code clearly conflicts with any extant legislation, it (the Code) should be amended so as to forestall widespread disregard of its provisions. We also encourage periodic updates of the provisions of the Code, so as to assure that same conform with relevant statutes and international best practices.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT LAW: Collective Agreement (Ganiu Lawal & 3 others vs. Federated Steel Mills Limited, 2014) 42 N.L.L.R. Pt 130, P. 306 NIC

Facts:

- The claimants’ complaint was against the right of the defendant to terminate their employment in furtherance to a collective agreement which was reached between the Association of Metal Products, Iron and Steel Employers of Nigeria (AMPISEN) and Steel and Engineering Workers’ Union of Nigeria (SEWUN).

- The position of the defendant was that because the claimants were accredited members of SEWUN and they paid their dues regularly to the Union; they are bound by the terms and conditions in the collective agreement.

Issues

- Whether or not the Collective Agreement between Association of Metal Products, Iron and Steel Employers of Nigeria (AMPISEN) and Steel and Engineering Workers’ Union of Nigeria (SEWUN) was enforceable on the claimants; thereby making the termination of the claimants’ employment by the defendant proper.

The Judgement

On jurisdiction of the National Industrial Court over interpretation and application of Collective Agreement:-

By the provisions of section 254C of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 as amended by third Alteration Act 2010, the National Industrial Court has exclusive jurisdiction in civil causes and matters relating to the determination of any question as to the interpretation and application of any Collective Agreement.

On definition of Collective Agreement:-

Section 54 of the National Industrial Court Act 2006 defines Collective Agreement as: any agreement in writing regarding working conditions and terms of employment concluded between:

- An organisation of employers or an organisation and representing employers (or an association of such organisations) on the one part, and

- An organisation of employees or an organisation and representing employees (or an association of such organisations) on the other part.

From the above provisions, therefore, the Court has unfettered jurisdiction to interpret the Collective Agreement between AMPISEN and SEWUN.

In the instant case, the claimants being members of SEWUN were covered by the Collective Agreement entered into by SEWUN with AMPISEN. Thus, the Collective Agreement is applicable to the claimants. See: ASCSN vs. Ho. Minister of Works & Ors (2011) 22 NLLR pt. 63, p 493

Final Judgment:-

The Judge held the Collective Agreement between AMPISEN and SEWUN was binding on the claimants; consequently their compulsory retirement was proper. The claimants’ suit was, accordingly, dismissed.

OPINION:

Parties are bound by their agreement and what has been done by agreement can only be undone by another agreement.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

1) Theme: Entrepreneurship Development Workshop for Managers and Potentials Retirees

Date: 15th – 17th November, 2016

Venue: NECA Learning Centre

Fee: N110,500 (NECA Members) N115,500 (Non-NECA members)

Time: 9:00am – 4:00pm

2) Theme: Negotiation: Strategy for Business Transaction and Relationship

Date: 24th – 25th November, 2016

Venue: NECA Learning Centre

Fee: N82,500 (NECA Members) N87,500 (Non-NECA members)

Time: 9:00am – 4:00pm

For further details please contact Adewale (08069720364) adewale@neca.org.ng Visit www.neca.org.ng

| For Advert Placement: kindly contact Timothy Olawale on tim@neca.org.ng, 08033435439 |

Recent Comments