Business Essential January 2018 Edition

Macroeconomics Outlook for Nigeria in 2018

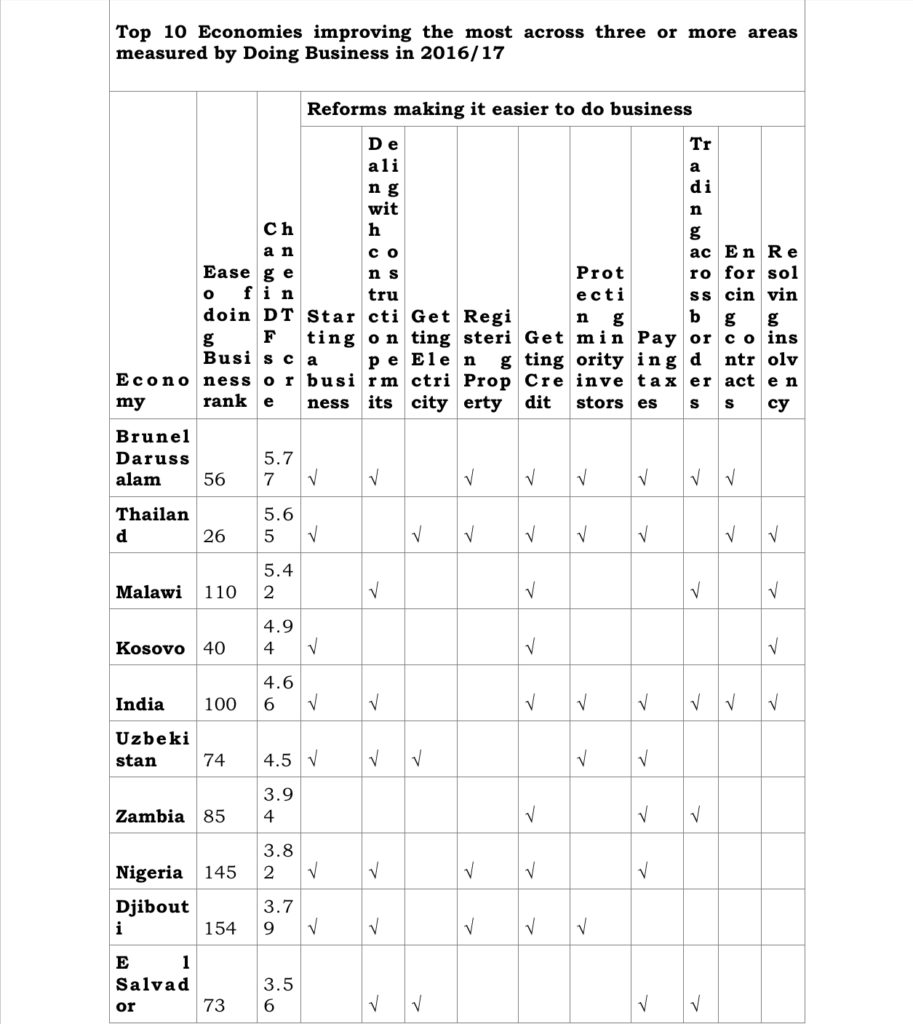

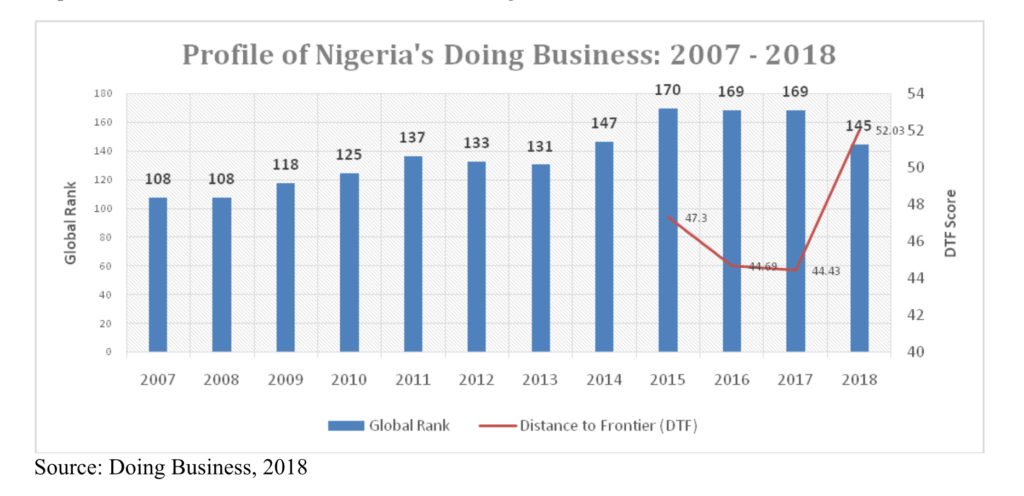

NB: Economies are selected on the basis of the number of reforms and ranked on how much their distance to frontier (DTF) score improved. Doing Business selected economies that implemented reforms making it easier to do business in three or more of the 10 areas included in this year’s aggregate distance to frontier score. Regulatory changes making it more difficult to do business are subtracted from the number of those making it easier.

Second, Doing Business ranks these economies on the increase in their distance to frontier score due to reforms from the previous year (the impact due to changes in income per capita and the lending rate is excluded). The improvement in their score is calculated not by using the data published in 2016 but by using comparable data that capture data revisions and methodology changes.

The choice of the most improved economies is determined by the largest improvements in the distance to frontier score among those with at least three reforms.

Business Implications

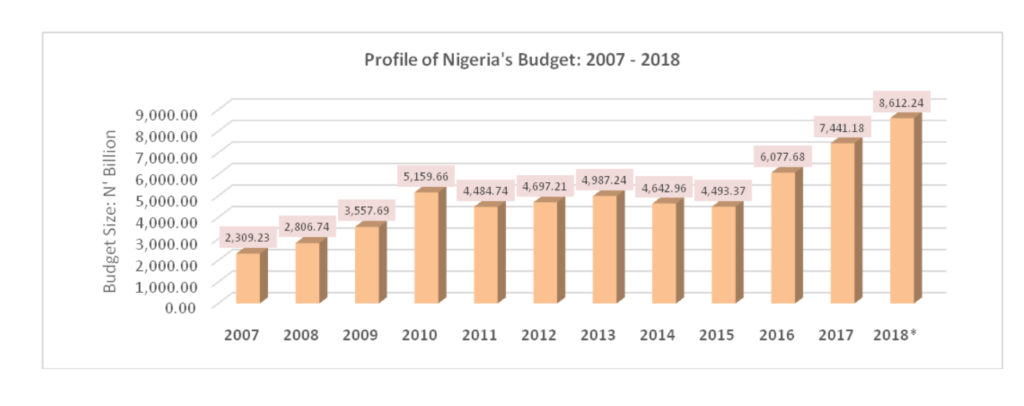

Global economic growth prospects have improved modestly due to stronger US growth expectations, exit of some large economies (e.g. Brazil and Russia) from recession, and rising commodity prices.

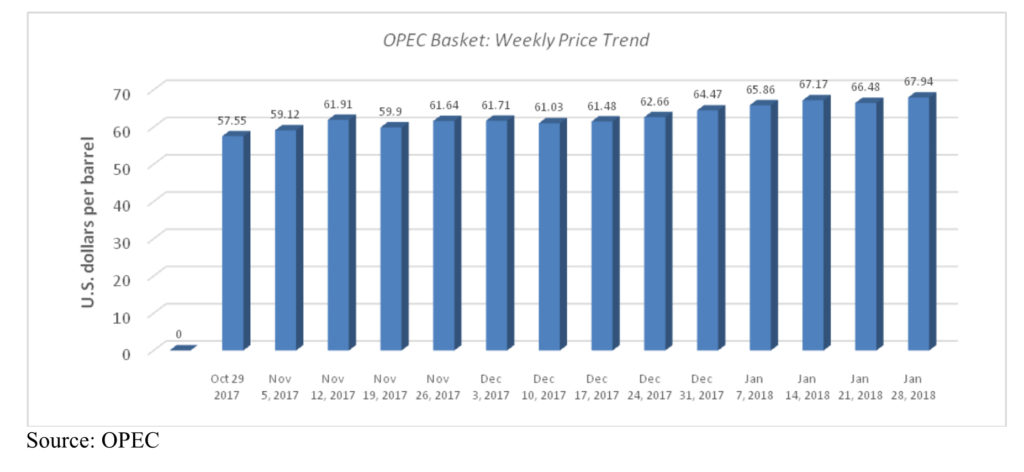

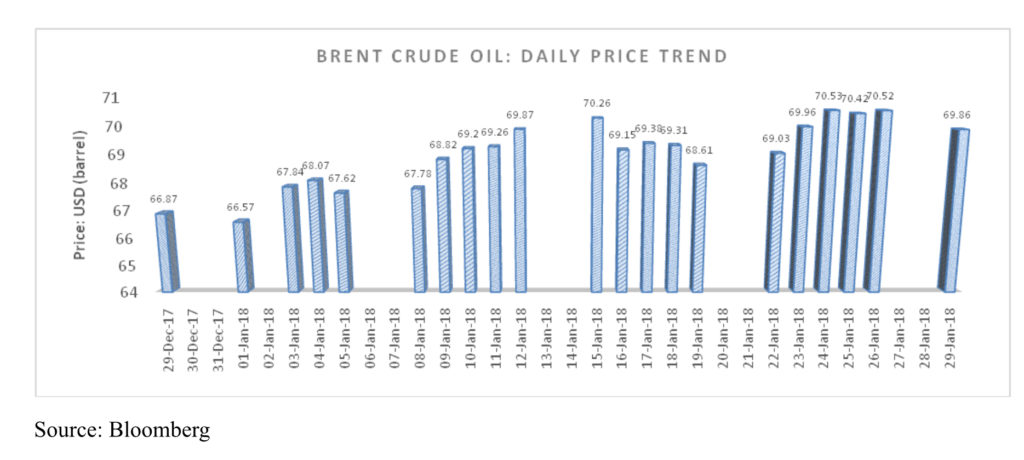

Oil prices have surged to $70pb beyond 2017 expectations, offering Nigeria some respite and suggesting a better economic outlook in 2018.

Two key areas of positive policy impact have been doing business reforms that resulted in Nigeria moving up 24 places on WB DB rankings; and greater FX liquidity aided by rising oil prices.

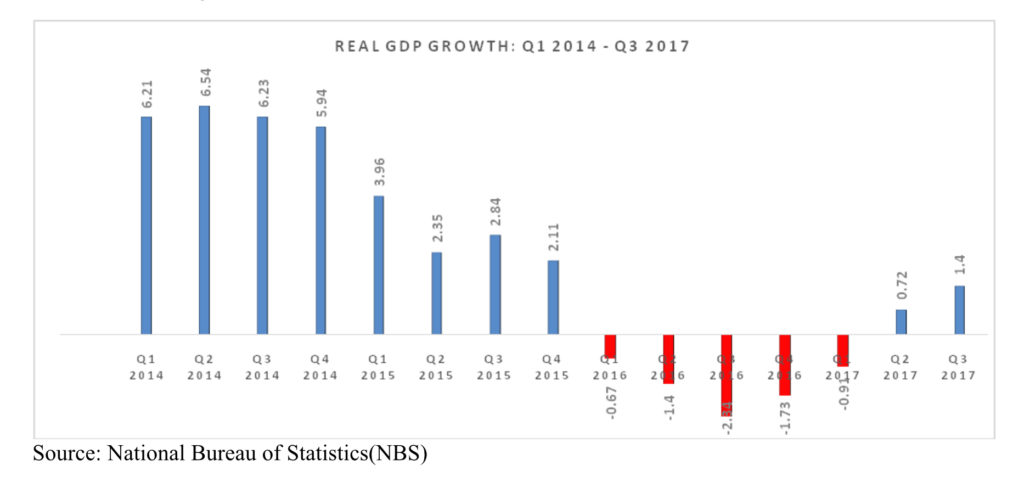

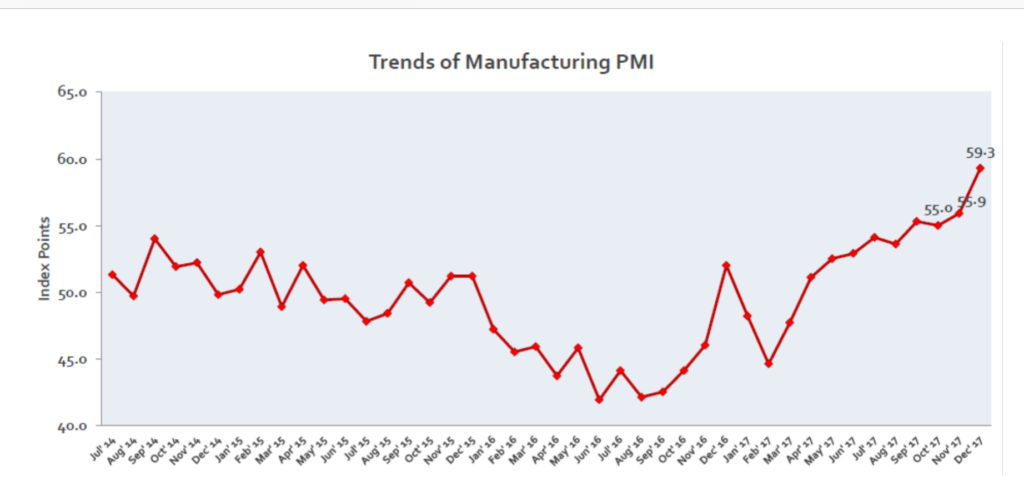

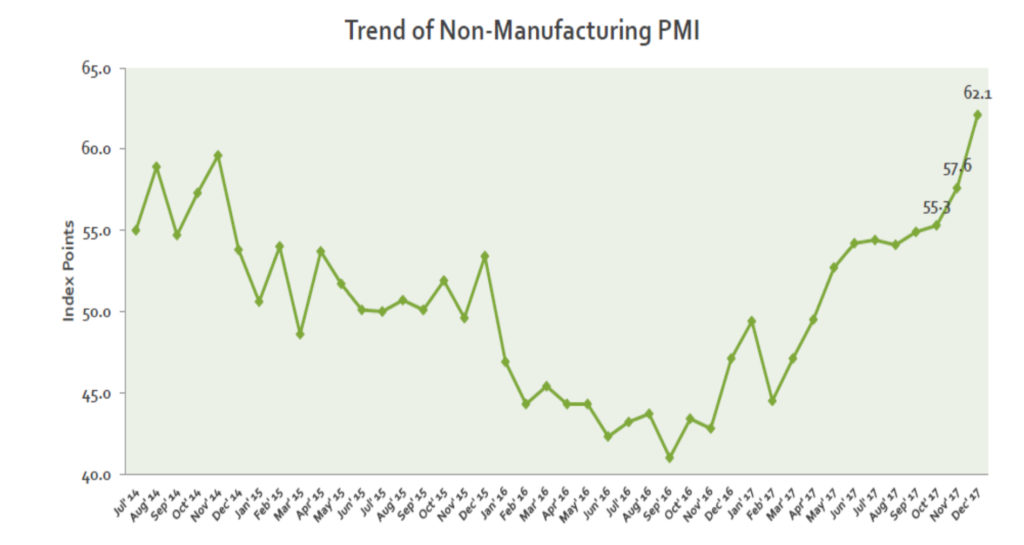

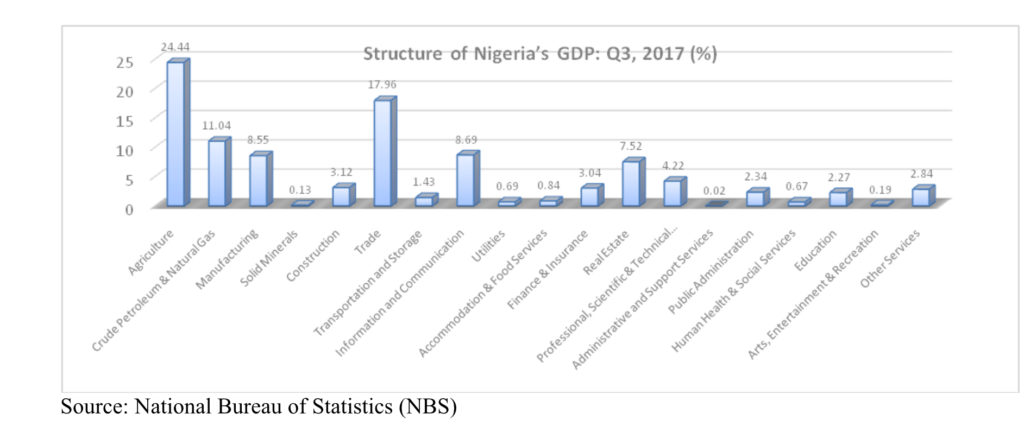

The PMI generally suggests a better outlook for manufacturing and non-manufacturing GDP, even though these expectations were yet to manifest in Q3 GDP. The current growth numbers remain essentially about oil prices and production.

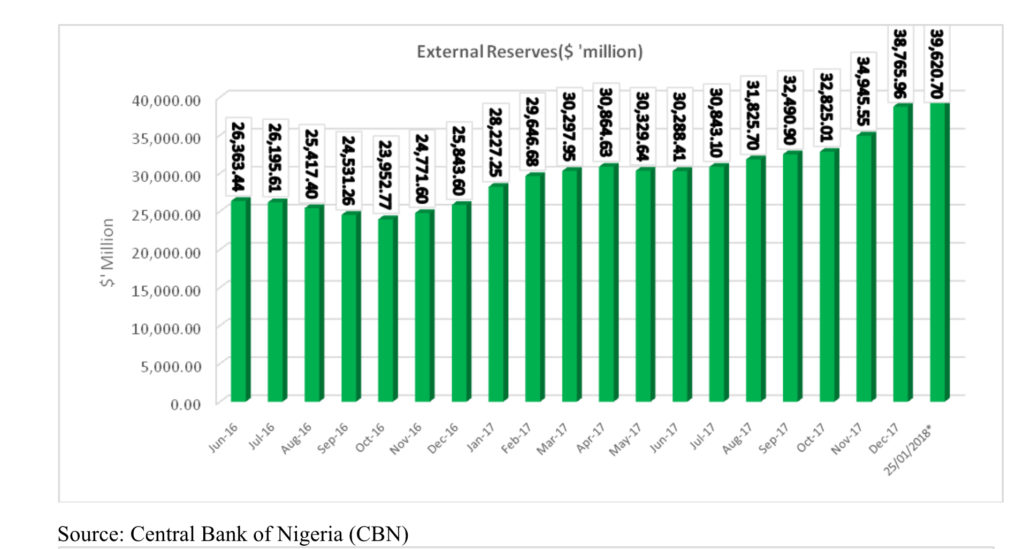

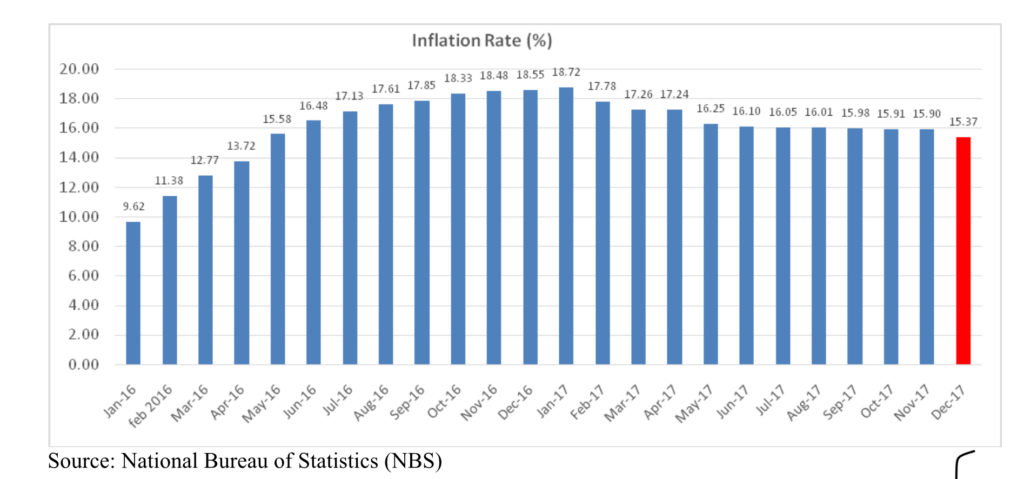

The positive macroeconomic elements include oil price and production volumes, moderating inflation (though domestic food inflation remains high), higher FX reserves and stable FX rates, rising PMIs and modest enhancements in capital flows. All of these suggest a better macroeconomic outlook in 2018, though Nigeria may have missed an opportunity for policy reforms.

The outlook for oil and gas sector in Nigeria has improved with the OPEC-Russia production cutbacks holding; oil prices reaching $60 per barrel; the truce in the Niger-Delta continuing to hold; and government appearing more willing to adopt private capital structures to fund oil and gas activities.

However risks remain with continuing threats from the Niger-Delta, especially as political activities intensify; and with global oil prices. Substantive oil and gas sector reform and legislation also remains outstanding.

Conclusion

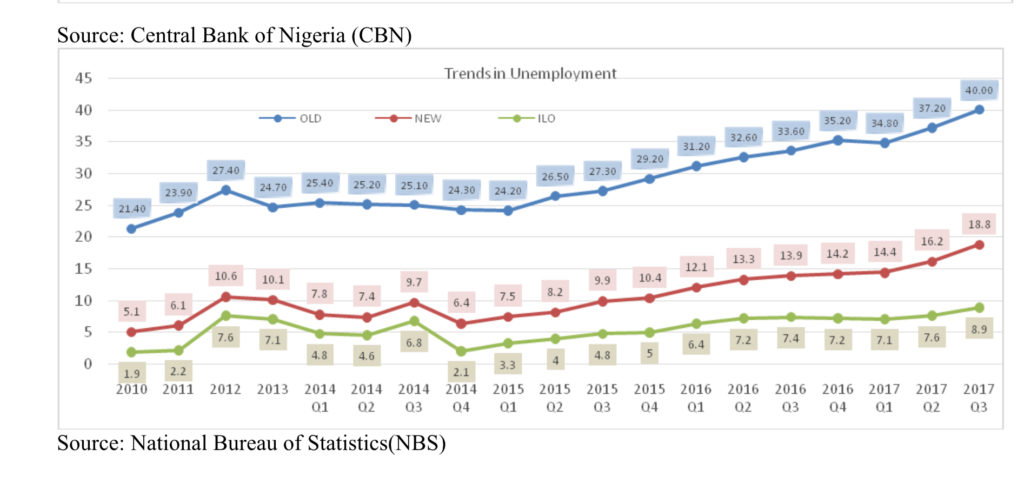

Nigeria is on the way to economic recovery after two quarters of growth but for the non-oil economy, it may yet be a long and patient walk rather than a quick dash! The GDP recovery in both Q2 and Q3 are firmly oil sector driven and in Q3, the non-oil economy returned into recession.

The outlook for 2018 may however be considered better as oil sector effects diffuse into other sectors as a result of higher government revenue and FX stability. This expectation is supported by PMI data and declining inflation.

The beginnings of another political cycle towards 2019 however suggest that aggressive policy may not be very likely. Increased election year spending may however improve the level of economic activity.

……….…………………………………………………………………………………………

How do you understand the concept of “Living Wage” and its practical implications?

Recent debate at international and national level is bringing back the concept of the living wage as a useful tool for companies operating globally, not only in the employment relationship with their employees, but also in managing their supply chain.

It is often presented as a means for effectively tackling wage challenges related to the lack of worker protection in weak governance areas. The concept itself is not new, but the current approach goes to some extent beyond the initial purposes for which it was designed. Some debates on national wage policies also make reference to living wages.

Given that some NGO and multi-stakeholder initiatives are pushing for the concept to be integrated into CSR strategies, companies and employers’ organisations need to be informed to respond adequately.

Generally, wage policy discussions encompass different concepts, including, among others, minimum wages, prevailing wages, average wages and living wages. When political debates arise on the definition of a minimum to be paid to employees, all concepts raise controversy from different quarters. This demonstrates how wage policies aimed at establishing a minimum wage require employers and employers’ organisations to be able to effectively influence the discussions.

Minimum wages represent the lowest level of pay, established through a minimum wage fixing system, to be paid to a worker by virtue of a contract of employment; prevailing wages are the rate currently paid to workers on the basis of their category and location; average wages are the mean salary paid to workers in a determined area or industry.

Note that Minimum wage can be set by:

Statute;

Decisions of the competent authority;

Decisions of wage boards or councils;

Industrial or labour courts or tribunals; or

Giving the force of law to provisions of collective agreements.

The Concept of Living wages

The concept presents problems because of its vague nature. As underlined below, its intrinsic lack of specification makes it ultimately difficult to handle and counterproductive in terms of improving worker protection and decreasing informality, as it was not initially designed to influence company wage policies.

The introduction of living wages is supposed to have increasingly positive effects on poverty alleviation, as more basic needs are included in its definition. However, this outcome has often been questioned. For instance, OECD research has found that the poorest households are those where no one is working and therefore neither living nor minimum wages would directly contribute to their poverty alleviation. There is also abundant literature arguing that minimum wages may in the medium and long term increase poverty and unemployment (particularly among workers with low productivity), and hinder business development. This could be said for living wages too, but given the diverse and wide definition of what can be considered as basic needs, living wages could be up to six times higher than minimum wages for low productivity sectors. This “excessively high minimum wage” could be even more counterproductive to employment creation and the competitiveness of companies and in the long term adversely affect the economic development of a country. Indeed, referring to living wages has to properly include consideration of national economic factors such as inflation, the cost of living, etc, the fluctuation of which depend on the country’s specific economy.

Beyond that, and although the “livability” concept has been used and developed at international level through Declarations, Conventions and Covenants, it remains highly problematic when applying it to companies.

Diverse definitions of living wages consistently refer to them as wages that allow workers to meet their own and their dependents’ basic needs.

Basic needs may include items such as:

Housing

Food

Childcare

Education

Transportation

Healthcare

Taxes

Saving for long term purchases and emergencies

Other basic necessities (social security)

Living wages and minimum wages

Living wages are essentially labour market interventions conceived as instruments of social regulation, without economic connotation, aimed at reducing inequalities and contributing to poverty alleviation. They were designed less to ensure fair compensation to employees, unlike minimum wages. Early attempts to introduce living wages were made in Australia and New Zealand at the beginning of the 20th century.

Also unlike the living wage, regulation on the minimum wage is widespread. The vague nature of the “livability” concept makes it difficult for countries to fix their minimum wages by referring exclusively to living wages. Only a few countries (for example, Indonesia and Colombia) use a reference to a living wage as part of a minimum wage setting system, together with other economic parameters.

Methodologies to measure living wages

The national poverty line level, set by governments, takes into account regional/ sectoral specificities.

The full market basket approach considers a complete basket of goods to meet the basic needs of a family, according to the composition of the household and the number of wage earners. The basket is meant to provide a 2500-3000 calorie diet per person per day.

The extrapolated market basket approach uses as a basis for measurement the food expenditure of an average consumer, multiplied by the number in the household and divided by the number of wage earners. Another (low) percentage is added to this amount for discretionary spending.

The relative income measure, based on the median pay of hourly earnings of a country. Half of the median pay would be considered as low pay. To avoid having to continuously update national hourly earnings, an additional amount of $2 per day (setting the poverty line) has been proposed as an absolute minimum below which half of the median pay cannot fall.

All these methodologies have pros and cons, but none seem to be appropriate in defining basic needs. Irrespective of the methodology, the living wage concept is more a social concept than a mathematical equation. For this reason, it is not suitable for companies to apply to their wage policy, especially for those located in weak governance areas, or in countries with low surveying and statistical capacities.

The ambiguity of the “livability” concept

The basic needs of workers and their families are diverse and it is difficult to define and measure them in an objective way (there is no mathematical formula which takes into account the diversities among households);

The idea of “livability” often gets confused with similar ideas, such as the subsistence wage, poverty line, and/or relative income. There is no agreement on these elements, or on other elements that can be considered as the basis for the “living” measurement, such as the household size, the number of wage earners, the level of needs (adequate, medium, low). Moreover, the methodologies outlined do not take into consideration other variations, namely the level of economic and social development of the country, the capacity of employers to pay, the productivity rate, the level of technology, the inflation rate, the unemployment rate; etc.

The intrinsic ambiguity of the concept makes it likely to lead to unrealistically high wage levels and to create dilemmas for companies, incurring negative consequences on job creation and competitiveness. It also affects the capacity of companies to survive in the formal economy. Furthermore, it can reduce the capacity of employers to hire and to pay workers, and therefore can decrease the number of jobs in a given industry.

It could lead to unjustified discrimination among workers, as it is not easy to objectivize the different elements in its definition. Its introduction could also alter perceptions of poverty in certain countries, so considering people not receiving the (higher) living wage poorer that they are in reality;

It risks shifting on to companies the responsibility that public authorities should assume in ensuring the basic needs of individuals by way of national social protection policies, to which employers already directly contribute (for instance national policies providing social insurance for health protection or social assistance covering housing, family care, etc.). Living wages subsidized through public financing would decrease the burden on the private sector, however with possible consequences on increased income taxes, which might in effect diminish the intended benefits. ;

Measurement of basic needs may pose greater difficulty along the supply chain, also because of the lack of data in weak governance areas.

Living wages in international law

References to living wages can be found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948 (Article 23, paragraph 3 states: “Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection”), and in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 1966 (Article 7 recognises that the right to “Remuneration which provides all workers, as a minimum, with: … (ii) A decent living for themselves and their families in accordance with the provisions of the present Covenant”.).

The principle of the “provision of an adequate living wage” is included in the Preamble to the Constitution of the International Labour Organization, and The Minimum Wage Fixing Convention (No. 131) and Recommendation (No. 135), 1970, deal with living wages (ILO Convention 131 established the level of minimum wage as the combination of both social (living) factors and economic ones (“the needs of workers and their families, taking into account the general level of wages in the country, the cost of living, social security benefits, and the relative living standards of other social groups” and “the requirement of economic development, levels of productivity and the desirability of attaining and maintaining a high level of employment”)).

Other references to living wages are to be found in the 1977 ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy(Paragraph 34 reads as follows: “When multinational enterprises operate in developing countries […] they should provide the best possible wages, benefits and conditions of work, within the framework of government policies. These should be related to the economic position of the enterprise, but should be at least adequate to satisfy the basic needs of the workers and their families. Where they provide workers with basic amenities such as housing, medical care or food, these amenities should be of a good standard”.) and in the 1976 OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

Nevertheless:

All these provisions have to be properly interpreted in their context and framework; none were conceived to create an international legal obligation on States or companies for a living wage.

Even if this concept appears to be a legitimate reference as a goal for public policies, none of these organizations, or UN Member States, have developed them in a concrete way, mainly due to the uncertainty and lack of practical approach that this concept lends itself to.

These references were initially introduced as objectives of public policies, as well as globally legitimate aspirations, rather than concrete obligations for companies within an employment relationship.

However, further pressure for engagement at international level can be seen in the OECD Guidelines which include a reference to“best possible wages” or, alternatively, wages covering “basic needs of the workers and their families”. They also state that “Enterprises should seek to prevent or mitigate an adverse impact where they have not contributed to that impact, when the impact is nevertheless directly linked to their operations, products or services by a business relationship. This is not intended to shift responsibility from the entity causing an adverse impact to the enterprise” […] Therefore it can be argued that this reference to wages applies beyond the direct relationship of multinational companies with their own employees in the country (This does not prevent companies’ action to “encourage, where practicable, business partners, including suppliers and sub-contractors, to apply principles of responsible business conduct compatible with the Guidelines”.).

Best approach for companies

While references to living wages are being used by some NGO and multi-stakeholder initiatives in monitoring labour standards in companies, businesses should take particular note of the drawbacks of such a concept.

Doing so would prevent them from having to ensure that suppliers compensate with wages that, depending on the elements used to define basic needs, could be two to three times prevailing wage rates in a given industry. As mentioned above, the concept lacks clarity and there is no consensus at national or international level. Attempted application of the concept could also create discrimination among workers, and, instead of being effective in resolving reputational or non-compliance risks in the supply chain, it could create additional difficulties for companies in weak governance areas.

The same could be said for SMEs striving to remain competitive and for whom an obligation to pay too high minimum wages would mean closing down, or shifting into the informal economy.

Therefore, it is highly recommended that companies look at more efficient alternatives as part of human rights/CSR, human resources, or wage policy strategies. In order to minimise reputational risk in supply chains or as a result of human resources policies for instance, more concrete references could be useful: national minimum wages where they exist, minimum wages as set up in collective agreements, or a general legal compliance approach.

Additionally, a multi-stakeholder approach to wage policies will be much more effective, with positive effects on the whole business environment and SMEs’ capacity to remain competitive. Indeed, it is important to bear in mind that challenges over compliance in the supply chain affect not just companies acting globally, but also other actors (international organisations, UN and non-UN agencies, NGOs and Trade Unions, regional organisations, consumers, business organisations, etc.) and this has to do with other factors such as the inefficiency and/or weakness of public institutions, including judicial systems; lack of appropriate adaptable legal frameworks; the absence of an attractive business environment; absence of a compliance culture; intensive migration phenomena; significant demographic change; lack of appropriate competences and qualifications; and widespread corruption, among others.

Culled from International Organisation of Employers (IOE) Guidance Paper On the Living Wage

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Law Review / Legal Opinion: The Inspection And Monitoring Of Production Companies Law Of Lagos State

Key highlights:

It is a 2007 Law of Lagos State, with a commencement date of 9th May 2007. The Law established a Department known as “Inspectorate and Monitoring Department” – s. 2

The purpose of the Department is to “monitor and inspect the activities and performance of industries, companies and factories in the State”. S.1

The scope of the Law is too wide as it extends to several aspects of the operations of a company i.e. HR, Factory Inspection, Injuries and Compensation, Environment, Federal Legislations, etc

The Department is to “conduct inspection of all industries and companies operating within the State in order to ensure their compliance with provisions as set out … all Federal and State Legislations applicable in the State”. S. 3. Furthermore, the Department also” issue a Certificate of Document to any factory” – S. 9

The implication here is that it had conferred upon itself the powers, roles and functions of the Inspectorate Division of the Federal Ministry of Labour & Employment

The Department is to “ensure protection of consumer rights for goods and services within the State in collaboration with relevant agencies”. S. 3

Fact: This is the functions of the Consumer Protection Council (CPC)

The Department would “set guidelines for: the supply of clean drinking water; washing facilities; etc” S. 3

Fact: This is within the ambit of the Lagos State Safety Water Regulatory Commission (LSWRC) and Lagos State Water Corporation.

By S. 4, the Department is empowered to: “inspect the Companies Fire Inspection Certificates, inspect and approve fire extinguishers, water hydrants, water reservoirs and equipment provided for fire fighting”

This is the responsibility of the Federal and State Fire Service. Thus, amounting to multiple regulatory bodies (1 from the Federal Government and 2 from Lagos State)

The Department is empowered to “take samples (solid, liquid, gases, etc where appropriate”. S.4

This role is being played by the Ministry of Environment through LASEPA.

By s. 11, “Any factory operating … with more than 50 workers in its employment MUST appoint a safety officer…”

This is a labour issue and an internal management issue for the company.

By s. 12, the company must notify the Department of an accident involving workers, building or other facilities within 48 hours of such occurrence(s)’. Thereafter, the Department will set-up a team to investigate the cause of the accident and where the company is found liable, it shall pay a fine not exceeding N500,000 (depending on the extent of damages occasioned by an accident in the premises), in addition to medical care at the expense of the company as well as monetary reliefs under the provisions of the Employees’ Compensation Act

This is within the purview of the NSITF

There are financial implications on companies:

N50,000 or more (depending on the workforce and annual return of the factory) as fine for a company operating without “documentation with the Department”. S. 7

N15,000 annual renewal fee for Certificate of Documentation – S. 9

N50,000 or 6 months imprisonment or both as penalty for obstructing any officer of the Department – s. 16

By Sections 13, 14 & 15, Officers from the Department have powers to inspect facilities, request for document, search premises, make seizures and even “arrest any person whom the officer has reason to believe has committed any offence” against the Law.

The Commissioner for Commerce and Industry in Lagos State has power to make Regulations – s. 17

Opinion

We admit that by Items 17,18 19 of the Concurrent Legislative List of the 1999 Constitution, the Federal Government and State Government can legislate on the same issue/subject matter.

However, where there are conflicts, the Federal Government prevails. The roles, functions and powers of the Department are already within an existing Federal Agency (CPC, NSITF, Inspectorate Division of the Federal Ministry of Labour & Employment, Federal Fire Service, etc). Therefore, companies should be able to challenge an incursion by Officers from the Department, created under the Lagos State Law.

Secondly, this could be a clarion call for Federal Government Agencies to be alive to their statutory responsibilities.

Furthermore, Employers should embark on a self-audit with the aim of ensuring that their operations are within the required standards.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

General Circular: Resurgent Activities Of The Lagos State Water Regulatory Commission (LSWRC)

Our Ref: NECA/SELA/H.8

29th January, 2018

TO: LAGOS-BASED MEMBER COMPANIES

Dear Sir/Madam

RESURGENT ACTIVITIES OF THE LAGOS STATE WATER REGULATORY COMMISSION (LSWRC)

The attention of your Association was drawn to the resurgence of activities by the Lagos State Water Regulatory Commission (LSWRC) through its requests for Companies’ compliance with Certification of Existing Water Treatment Facility and Certification of Existing Wastewater Treatment Facility. We have no objection to the regulation of these two items as the Lagos State Environmental Law had removed the role from LASEPA and conceded these to LSWRC.

However, there had been reported instances of further requests for payments of application / registration forms, license to abstract water and Permit for borehole. These and abstraction levies / rates, were items put on hold due to Organised Private Sector (OPS)’s engagement of the Governor, His Excellency, Mr. Akinwunmi Ambode on the matter on 13th April, 2017. The position of the OPS, in summary, was that it is the responsibility of Government to provide water for its citizens (corporate and residents), thus the Commission should cease further implementation of the Lagos State Water Regulatory Law (2012) and all associated activities / visits to Companies on the matter until the conclusion and feedback on the works of the Committee set up by the Governor.

The Committee is yet to advise the Governor to enable him take a stand on the matter. We, therefore, advise member-companies to restrict their dealings with the Commission to Water Treatment Facility and Wastewater Treatment Certifications. Requests for payments of application / registration forms, license to abstract water, permit for borehole and abstraction levies / rates are on hold until we receive feedback from the Governor.

Thank you

Yours faithfully,

Timothy Olawale

Ag. Director-General

cc: President, Vice Presidents, Treasurer – NECA

Director General, Manufacturer’s Association of Nigeria (MAN)

Director General, Nigeria Association of Chambers of Commerce, Industries, Mines and Agriculture (NACCIMA)

Lagos-based NECA members

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Judgment of the National Industrial Court: Group Life Insurance Benefits

Mr. Francis Owoade & Ors vs. Unity Bank Nigeria Plc, unreported Suit No. NICN/LA/224/2016

–

FACTS

The claimant had filed the action on 1st April 2016, praying for the following reliefs –

A declaration that the Group Life Insurance Benefits of the deceased, Mrs Omosola Oladoyin Owoade ought to be computed on the basis of her total annual emoluments and which includes her basic salary and other allowances.

A declaration that the Group Life Insurance Benefits of Mrs Omosola Oladoyin Owoade ought to be N6,441,252.12 being three (3) times her annual emoluments.

A declaration that it was wrongful and illegal for the defendant to make any deduction from the deceased’s Group Life Insurance Benefits.

An order directing the defendant to pay the balance of the Group Life Insurance benefits to the claimants in the sum of N5,606,095.81 with the interest at the rate of 27% per annum from September 2009 till judgment and thereafter at the rate of 6% per annum.

An order directing the defendant to refund the entire sum of money deducted from the deceased’s Group Life Insurance benefits.

The cost of this action assessed at N500, 000 (Five Hundred Thousand Naira).

ISSUES FOR CONSIDERATION

Whether the Group Life Insurance benefits of Mrs Omosola Owoade was not wrongly computed by the defendant.

Whether the Group Life Insurance benefit of Mrs Omosola Owoade can be subjected to any deduction by the defendant.

Whether the claimants are not entitled to their claim.

JUDGMENT

The Court held that the claimants’ case succeeds in terms of the following declarations and orders:

The court declared that the Group Life Insurance benefits of Mrs Omosola Oladoyin Owoade ought to be computed on the basis of her total annual basic salary, annual housing allowance and annual transport allowance.

The court declared that the Group Life Insurance benefits of Mrs Omosola Oladoyin Owoade ought to be N6, 063,837.12 being three times her annual emolument.

The defendant was ordered to pay the sum of N1, 223,837.89 being the balance of the Group Life Insurance benefits of Mrs Omosola Oladoyin Owoade.

The sum of One Million, Two Hundred and Twenty-Three Thousand, Eight Hundred and Thirty-Seven Naira, Eighty-Nine Kobo (N1, 223,837.89) only was ordered to be paid within 30 days of the judgment; failing which it shall attract interest at 10% per annum until fully paid.

There was no order as to cost

OPINION

The Pension Reform Act (PRA) 2014 requires every employer to maintain a Life Insurance Policy for its employees. A proper understanding of the law and its application is necessary, as it would have avoided litigation. Thus, training and re-training should be encouraged.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Upcoming Meetings of various Expert Committees

Committee of Legal Advisers and Company Secretaries (COLACS)

Date: Thursday, 8th February, 2018

Venue: NECA House

Time: 10:00am

Electricity Distribution Companies Meeting (DISCOS)

Date: Monday, 12th February, 2018

Venue: NECA House

Time: 10:00am

NECA Ibadan Geographical Group Meeting (IGG)

Date: Thursday, 22nd February, 2018

Venue: Rom Oil Mills Limited, Ibadan-ijebu-Ode Road, Idi Ayunre

Junction, Ibadan, Oyo State

Time: 10:00am

Annual Retreat of NECA’s Technical Committees

Theme: Strategies for Sustainable Enterprise Growth

Date: Friday 23rd – Saturday 24th March, 2018

Venue: Park Inn By Radisson, Kuto, Abeokuta, Ogun State

Participation fee: N95,000.00

Recent Comments