Business Essential May Edition

Welcome to the May 2019 edition of Business Essentials. In this edition, we reviewed the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) recently released GDP Report for Q1, 2019, with data reflecting the strongest first quarter performance observed since 2015. We examined the report of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting for May which showed that the overall medium-term outlook for the global economy remains mixed and uncertain, the Consumer Price Index for April 2019 and World Economic Forum’s Report which amongst other things, ranked Nigeria among 103 countries globally with slow social progress.

Rising debt portfolio of Nigeria and other African countries continues to be a growing concern and questions on the sustainability of the debts has consistently been raised by the IMF, the World Bank and Financial Analysts. In this edition, we presented a special report by the Brookings Institution which x-rayed the increasing debt of African countries from a historical perspective and current realities, while also suggesting ways in which Nigeria and other African countries can escape the impending crisis.

We presented an overview of Employee Compensation, looking at the definition of compensation according to the Personal Income Tax Act CAP P8 LFN (2004). The report examined the compensation types, other considerations for employee compensation and how the compensation structure of an organization impacts on its finances. The report further advises on the need for adequate tax planning in defining an organisation’s employee compensation structure in order to take advantage of the tax planning opportunities available in the respective tax laws.

Also in this edition are pictures from the inauguration of the Committee on Corporate Communications and Public Affairs which held on Wednesday, 22nd May at NECA House.

Our regular Law Report Review, Upcoming Learning & Development programmes and other activities at the Secretariat were not left out.

Have a pleasant reading.

Adewale Oyerinde

Editor

In this Issue:

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) GDP Q1 2019 Report, April CPI, MPC Report, CBN PMI Survey & World Economic Forum Report

- Special Report: Is a Debt Crisis Looming in Africa?

- Tax, Regulatory and other Considerations for Employee Compensation

- Pictures from the Inauguration of the Technical Committee on Corporate Communications and Public Affairs (CC&PA)

NATIONAL BUREAU OF STATISTICS (NBS) GDP Q1, 2019, APRIL CPI, MPC REPORT, CBN PMI SURVEY & WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM REPORT

Overview of GDP in Quarter One 2019

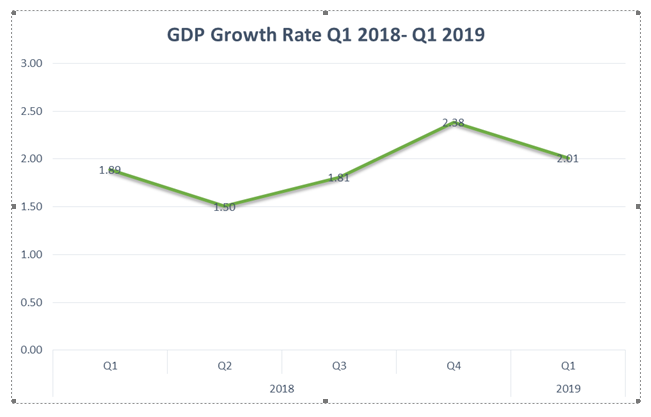

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew by 2.01% (year-on-year), in real terms, in the first quarter of 2019. The figure reflected the strongest first quarter performance observed since 2015. Compared to the first quarter of 2018, which recorded real GDP growth rate of 1.89%, Q1 2019 growth rate represented an increase of 0.12% points. However, relative to the preceding quarter (fourth quarter of 2018), real GDP growth rate retracted by –0.38% points.

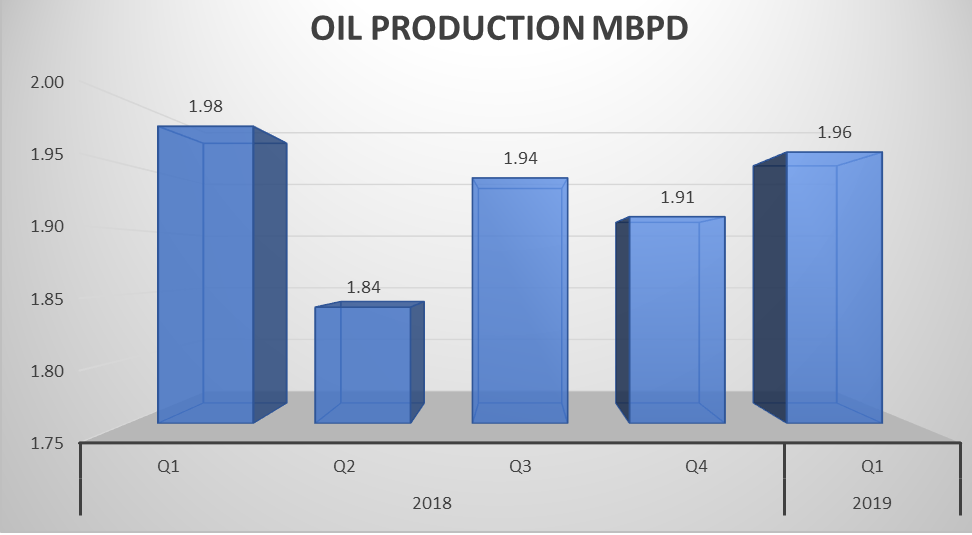

The average daily oil production stood at 1.96million barrels per day (mbpd), lower than the average daily production of 1.98mbpd recorded in the same quarter of 2018 by -0.02mbpd but higher than the fourth quarter 2018 production volume by 0.05mbpd. The level of oil output during the quarter was the highest recorded over the past one year and the second highest since mid-2017.

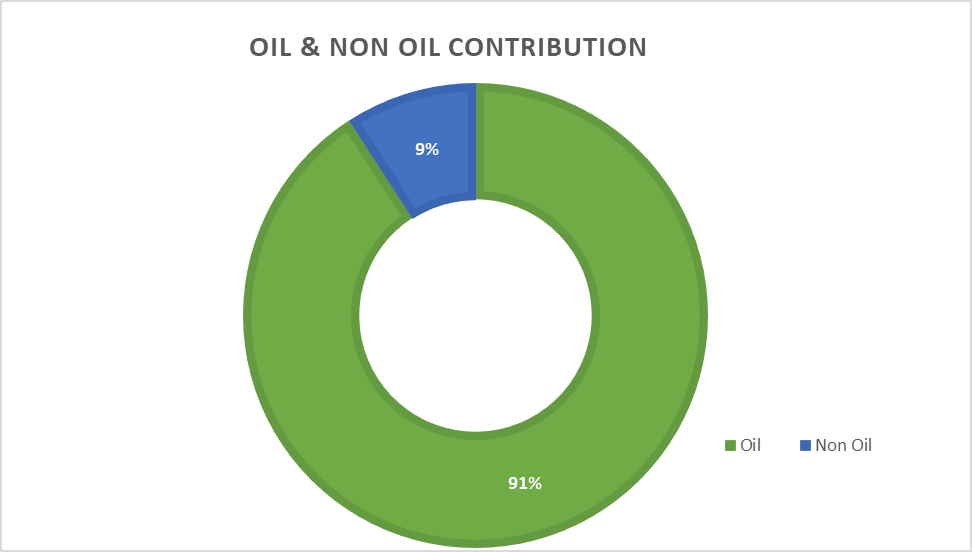

Real GDP growth in the oil sector was –2.40% (year-on-year) in Q1 2019 indicating a decrease by –16.43% points relative to the rate recorded in the corresponding quarter of 2018. Growth decreased by –0.79% points when compared to Q4 2018 which was –1.62%. Quarter-on-Quarter, the oil sector recorded a growth rate of 11.60% in Q1 2019. The Oil sector contributed 9.14% to total real GDP in Q1 2019, down from figures recorded in the corresponding period of 2018 but up compared to the preceding quarter Q1 2018 & Q4 2108, where it contributed 9.55% and 7.06% respectively.

The non-oil sector grew by 2.47% in real terms during the reference quarter. This was 1.72% points higher compared to the rate recorded in the same quarter of 2018 but -0.23% points lower than the fourth quarter of 2018. During the quarter, the sector was driven mainly by Information and communication technology. Other drivers were Agriculture, Transportation and Storage, Trade and Construction. In real terms, the non-oil sector contributed 90.86% to the nation’s GDP, higher than recorded in the first quarter of 2018 (90.45%) but lower than the fourth quarter of 2018 (92.94%).

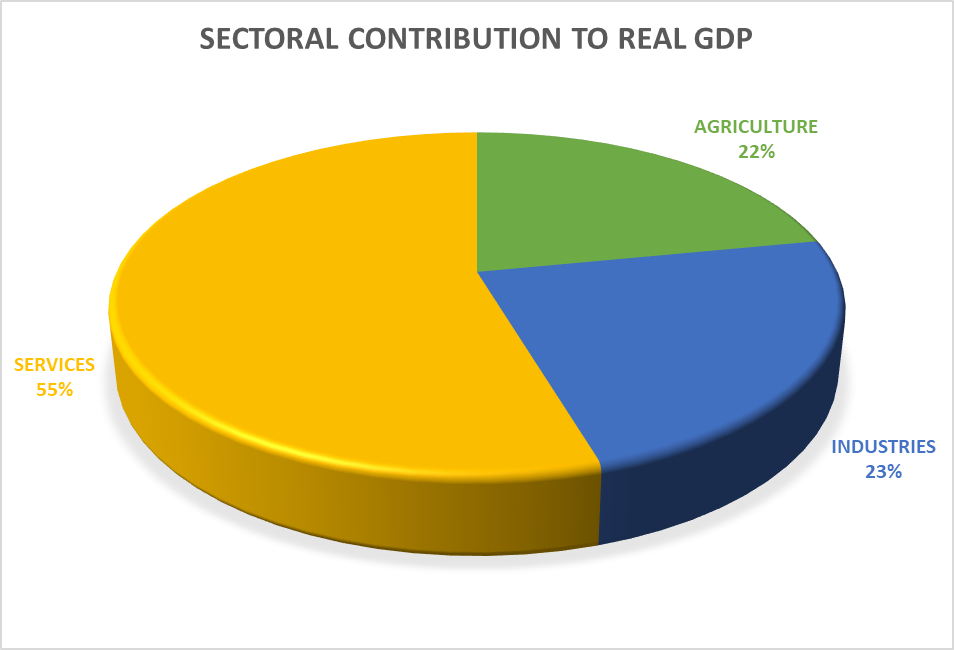

Agriculture contributed 21.91% to overall GDP in real terms during the Q1 2019, lower than the contribution Q4 of 2018 (26.15%), but higher than the first quarter of 2018 (21.66%). Service Sector contributed 54.60% to GDP in Q1, 2019 marginally higher than all the previous quarters in 2018 (Q1-Q4, 2018: 54.38%, 53.97%, 48.79%, 53.62% respectively).The contribution of Industries to Q1 2019, GDP increase to 23.49% from 20.24% in Q4 2018. Comparing the Q4, 2018 with Q1, 2019 contribution of each sector to the GDP, the report shows that both the Industries and Service Sector improved while the Agricultural Sector decline

Monetary Policy Committee Report

The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) met on the 20th and 21st of May 2019, amidst uncertainties in the global financial, economic and political environments. The report of the Committee showed overall medium term outlook for the global economy remains mixed and uncertain with growing indications of persistent macroeconomic vulnerabilities, global financial market fragilities, accommodative monetary policy, policy uncertainties and weakening global output.

Data on the domestic economy suggests some fragility in output growth during the second quarter of 2019 with improved outlook for the rest of the year. Accordingly, revised output projections indicate that the economy would grow by 2.1 per cent according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2.2 per cent by the World Bank and 2.38 per cent by the CBN in 2019. This outlook is hinged on the following key factors: the effective implementation of the Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP); supportive monetary policy; enhanced flow of credit to the real sector; sustained stability of the exchange rate; and improved fiscal buffers; amongst others. The Committee, thus, expects that monetary policy would focus on improving access to credit, reducing unemployment and stimulating economic growth.

The Committee enjoined the Federal government to urgently build fiscal buffers through a more realistic benchmark oil price for the Federal Budget. The MPC noted the 2.01 per cent growth in real GDP during the first quarter of 2019 compared with 1.89 per cent in the corresponding quarter of 2018. Although output growth in the first quarter was slower than 2.38 per cent recorded in the preceding quarter, it emphasized that actual output remains well below the economy’s long-run potential, indicating the existence of spare capacity for non-inflationary growth in the economy, an opportunity which should be explored through increased credit delivery to the private sector.

The Committee noted the developments in the monetary aggregates and enjoined the Bank to initiate moves towards improving lending to the private sector and urged other intermediary institutions in the financial sector to support these initiatives by improving their credit delivery to boost output growth. The Committee called on CBN management to urgently put in place modalities to promote Consumer, and Mortgage lending in the Nigerian economy, noting that doing this will greatly and positively impact on the flow of credit and ultimately result in output growth.

Consequently, the MPC decided against the backdrop of these developments by a vote of 9 members out of 11, to hold all parameters of monetary policy constant. Two members voted, however, to reduce the monetary policy rate by 25 basis points.

In summary, the MPC voted to:

I. Retain the MPR at 13.50 per cent;

II. Retain the asymmetric corridor of +200/-500 basis points around the MPR;

III. Retain the CRR at 22.5 per cent; and

IV. Retain the Liquidity Ratio at 30 per cent.

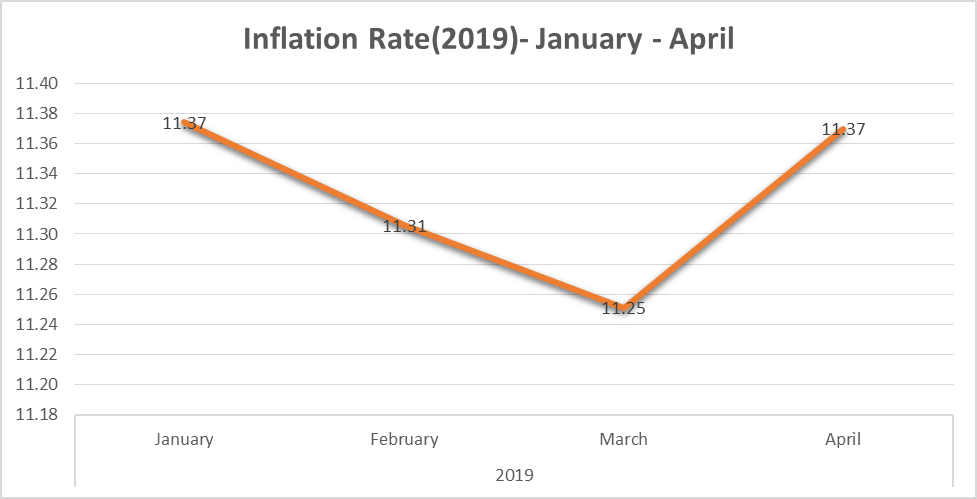

The NBS Consumer Price Index (CPI), April, 2019

The Consumer Price Index increased for the first time in 2019 to 11.37% (year on year) in April, 2019. The CPI, which measures the composite changes in the prices of consumer goods and services purchased by households over a period, increased by 0.12 percent compared with value recorded in March 2019(11.25%). The rebounds in the CPI was triggered by higher food prices, which accelerated the most in the last one year.

Similarly, food inflation rose to 13.70 percent from a year earlier in April compared with 13.45 percent recorded in March after three consecutive months of disinflation, even as core inflation, which captures all items but exempts the prices of volatile agricultural produce, moderated to 9.3 percent to reach its lowest level in over three years.

On month-on-month basis, the country’s headline inflation sustained its upward trend by 0.94 percent in April from 0.79 percent recorded in the previous month. Food inflation spiked to 1.14 percent from 0.88 percent, while core inflation rose by 0.70 percent from 0.53 percent. Likewise, urban inflation rose faster in April to 11.70 percent from the same period last year compared with 11.54 percent achieved in March, while rural inflation accelerated to 11.08 percent on year-on-year basis from 10.99 percent.

Also, on month-on-month basis, urban inflation continued to rise quickly to 1 percent in April as against 0.81 percent recorded in March, while rural inflation worsened in the review month to 0.90 percent from 0.77 percent in March.

CBN Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index

The latest report by CBN on the Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) showed 57.7 index points in April 2019. This indicates an expansion in the manufacturing sector for the twenty-fifth consecutive month. The index grew at a faster pace when compared to the previous month (57.4points). The April 2019 PMI survey was conducted by the Statistics Department of the Central Bank of Nigeria during the period April 9-13, 2019. A composite PMI above 50 points indicates that the manufacturing/non-manufacturing economy is generally expanding, 50 points indicates no change and below 50 points indicates that it is generally contracting. The subsectors reporting growth are listed in the order of highest to lowest growth, while those reporting contraction are listed in the order of the highest to the lowest contraction.

World Economic Forum Report

Recent research on Inclusive Development Index (IDI) by the World Economic Forum (WEF) in 2018 ranked Nigeria among 103 countries globally with slow social progress, even in the presence of economic progress in those countries. Figures from National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) indicate that Nigeria’s GDP advanced 2.4 percent year on- year in the last quarter of 2018, while Foreign Exchange Reserves stood at $44.7 billion in April, 2019, indicating some progress in Nigeria’s economic trajectory.

Nigeria was recently tagged as the world capital of poverty by having the highest number of people in extreme poverty according Brookings Institution. At the end of May 2018, the report said Nigeria had about 87 million people in extreme poverty, compared with India’s 73 million. It also said that extreme poverty in Nigeria is growing by six people every minute. This is in spite of abundant resources in the country. A year later, precisely late March 2019, a report by Steve Hanke, an economist from John Hopkins University in Baltimore, United States, ranked Nigeria as the sixth most miserable country in the world. The Misery Index was calculated using economic indices including unemployment, inflation and bank lending rates. This has further widened social inequality and erosion of social cohesion despite having the second lowest level of public debt among emerging economies (18.6%).

SPECIAL REPORT: IS A DEBT CRISIS LOOMING IN AFRICA?

Concerns about an impending debt crisis in Africa are rising alongside the region’s growing debt levels. As of 2017, 19 African countries have exceeded the 60 percent debt-to-GDP threshold set by the African Monetary Co-operation Program (AMCP) for developing economies, while 24 countries have surpassed the 55 percent debt-to-GDP ratio suggested by the International Monetary Fund. Surpassing this threshold means that these countries are highly vulnerable to economic changes and their governments have a reduced ability to provide support to the economy in the event of a recession.

While debt is a global issue, Africa’s past debt crises have been devastating, creating the need to cautiously monitor this recent debt buildup. There are parallels between the present rising debt in Africa and the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative period that proffer solutions for prevent another crisis.

Figure 1: Government debt as a percent of GDP for African countries, 2017

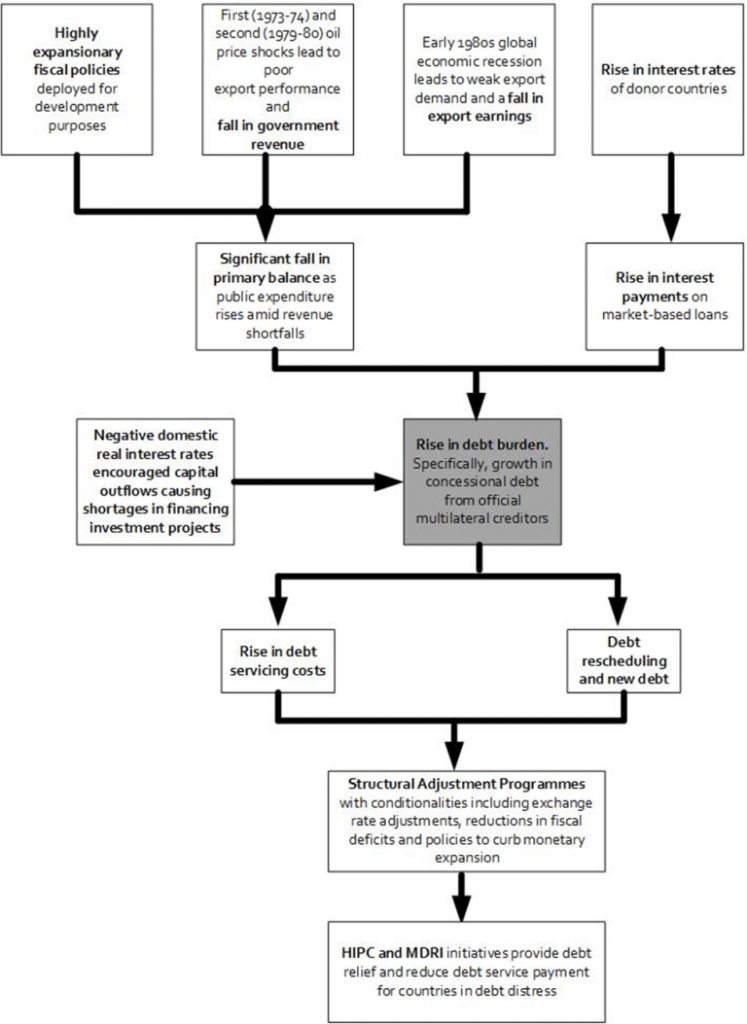

The events that led to HIPC and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) started in the 1960s from a public spending spree by recently independent countries to stimulate their economies through rapid investment in industry and infrastructure projects (Figure 2). Commodity booms and heavy use of external debt supported this spending as policy leaders relied on future export earnings and economic growth to improve the capacity to service the debt. Notably, those countries did not reduce expenditures during negative commodity shocks and instead took on more loans. Three key factors drove the subsequent debt crisis—the 1980s global recession, the rise in interest rates in developed countries, and a decline in real net capital inflows, which was largely due to the real negative interest rate in many countries.

As a result, the external debt-to-gross national income (GNI) ratio for the continent rose from 49 percent in 1980 to 104 percent in 1987. The World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Program attempted to tackle the problems by reducing fiscal deficits through expenditure cuts, but these austerity measures had severe, adverse impacts on social spending (and thus on livelihoods), and resulted in large current account deficits, astronomical inflation, and depressed currencies. This situation led the World Bank and the IMF to establish the HIPC initiative in 1996 to provide debt relief and reduce debt service payments of up to 80 percent for eligible countries.

Figure 2. Description of events leading to Africa’s indebtedness in the 1970s and early 1980s

In addition, in 2005 the IMF initiated the MDRI, which provided full debt relief on eligible debt. Under HIPC and MDRI, 36 countries, including 30 African ones, reached the completion point (the phase at which total debt relief is received) resulting in debt relief of $99 billion by the end of 2017. Between 1999 and 2008 alone, HIPC and MDRI reduced the external debt-to-GNI ratio for the region from 119 percent to 45 percent.

IS AFRICA HEADING BACK TO THE HIPC ERA?

Not quite…but the present composition of debt is worrisome.

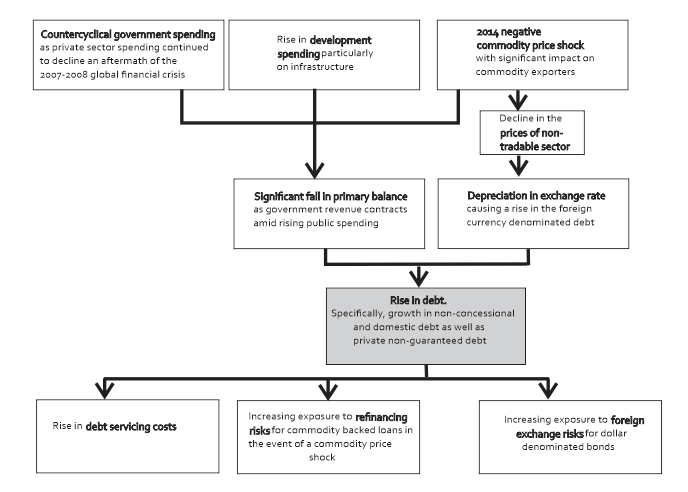

The drivers of the present rising debt situation are similar to, but not the same as, that of the HIPC era (see Figure 3). In the wake of the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, governments deployed countercyclical spending to compensate for depressed private sector spending.

Another key driver was the huge rise in public expenditure on infrastructure—an effort to close the huge infrastructure gap (Africa needs to spend $93 billion annually from 2009 to 2020 to close its infrastructure gap). Of greatest magnitude was the 2014 negative commodity price shock, which dramatically reduced government revenues.

Figure 3. Description of events leading to the present debt situation

The aforementioned factors led to a decline in primary balance from 3.9 percent of GDP between 2006 and 2008 to -6.9 percent of GDP by 2015 with countries borrowing excessively to meet public expenditure. The commodity price shock caused a depreciation in the exchange rate for several countries. Following the depreciation, foreign currency-denominated debt increased significantly.

A distinctive feature of the ongoing rising debt problem is the composition of debt. Countries are tilting away from official multilateral creditors who come with stringent conditions and toward non-concessional debt with relatively higher interest rates and lower maturities. This trend raises concerns around debt sustainability given the possibility of higher refinancing risks—particularly for commodity-backed loans in the event of a commodity price shock—and foreign exchange risks.

Furthermore, private non-guaranteed debt has grown: Between 2006 and 2017, private sector external loans tripled from $35 billion to $110 billion. This growth could result in balance of payment problems as the private sector competes with the public sector for foreign exchange. Also, it may increase the government’s exposure to risks associated with contingent liabilities in the event of a default.

Another noteworthy trend is that countries witnessing a deepening of their financial markets are increasingly borrowing from their domestic debt market. South Africa, Kenya, and Nigeria, among others, have been issuing long-term bonds for large capital projects such as roads and hospitals. While tapping into the domestic debt market provides a sound alternative and does not expose the country to foreign exchange risk, it has the potential to crowd out private sector borrowing, thus hampering investment and output growth.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

The rising debt burden across the continent is clearly a concern for borrowers, lenders, and the broader international community. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the present debt level is far below that of the HIPC era: In 2017, public debt as a percent of GDP in sub-Saharan Africa was 45.9 percent relative to the 117 percent external debt-to-GNI ratio of 1995. Also noteworthy is that sovereign debt financing is inevitable given that African countries budgetary resources are insufficient to finance their vast development agenda. Thus, in ensuring that all stakeholders become more prudent, we recommend the following:

1. Better debt management

Despite the spike in sovereign borrowing, sub-Saharan Africa’s performance in debt management has consistently declined from 3.34 in 2014 to 3.08 in 2017 (on a rating scale from 1 to 6). For those without, authorities need to design and implement formal and legal frameworks for debt management that stipulate borrowing targets and preferences for borrowing sources. Countries can tap into the support programs provided by the IMF and the World Bank. Also, establishing systems and processes to ensure up-to-date debt recording and timely debt service payments is necessary for maintaining accountability, transparency, and sustainable debt levels. With the characteristics of debt changing significantly (e.g., the rise of nontraditional lenders, growth in domestic debt, and increase in private nonguaranteed debt), debt management authorities must utilize more sophisticated means to better analyze the costs and risks of these changes. Overall, these sound debt management practices should be extended to the subnational level and state-owned enterprises to ensure more comprehensive management.

2. The issuance of “debt-management” financial instruments

Local authorities should issue debt instruments that can better manage the debt level. For instance, the issuance of the sukuk bond— Islamic bonds that allow investors to generate returns by having a share in the ownership of the asset linked to the investment rather than earning interest from the bond—that is tied to capital projects in Nigeria curtails the improper use of debt. Also, they should consider a state-contingent debt instrument that links debt service to predefined macroeconomic variables, such as GDP growth and changes in commodity prices. Thus, shocks that negatively impact fiscal space, such as economic recession, will not increase the debt service burden of the issuing country.

3. More responsible lending

A debt crisis poses risks to borrowers and lenders alike. For this reason, lenders should focus on making more responsible lending decisions following due process in authorizing loans and possibly stipulating limits. Presently, the codes of conduct that address irresponsible lending such as the G-20’s Operational Guidelines for Sustainable Financing (2017) and the OECD’s Recommendation on Sustainable Lending Practices and Officially Supported Exports Credits (2018) are only binding on traditional creditors. A first step should be the development of new codes or a revision of existing ones to adjust to nontraditional actors. In addition, these codes should be enshrined in law so that participating countries adhere to them. Better coordination, more engagement, and increased information-sharing between traditional and nontraditional lenders is also crucial.

4. Streamlining procedures

The World Bank and IMF impose numerous, stringent, and time-consuming conditions on developing countries in order to access development finance, many of which advocate for controversial reforms such as privatization and trade liberalization policies that are not in accordance with the will of the developing country. Streamlining the lending process to reduce the number and scope of conditions to respect national sovereignty and reduce the burden associated with accessing loans is of the utmost importance. The World Bank could also increase the lending program to middle-income countries that still face development challenges like inequality, unplanned urbanization, and a weak private sector. Better engagement with these countries will enable them to consolidate their development gains and make substantial economic and social progress.

Source: The Brookings Institution

TAX REGULATORY AND OTHER CONSIDERATIONS FOR EMPLOYEE COMPENSATION

Employee compensation can be said to be the benefit or payment made to an employee by the employer, for service rendered by the employee based on the terms of the contract of employment of the employee. Employee compensation, also referred to as employee emolument, may come in various forms ranging from cash emolument such as salary, bonus, allowances etc., to non-cash emolument such as employee share-award, provision of accommodation, assets, etc. for the employee’s benefit. These emoluments leave different tax footprints, depending on the form of such items and how they are implemented by the employer.

In Nigeria, employers of labour have certain regulatory obligations with respect to their employees. These could be tax-related, such as deduction and remittance of Pay-As-You-Earn (PAYE) tax on employee emolument, or related to social security provisions for employee benefit such as pension fund contributions and employee compensation relief.

This article discusses the various forms of employee compensation and some of the related tax and regulatory obligations of the employer.

Overview of Employee Compensation

Organisations desire to adopt the best practices in relation to compensation packages for their employees. This usually comes at a huge cost to such organizations. Hence, various methods for compensating employees are developed in order to reduce employment cost whilst attracting best hands in the labour market. These methods may be in the form of cash compensations, non-cash compensations or use of both methods.

Cash Compensations

This is the most common form of compensation. It is made in form of basic salary, transport allowance, housing allowance, lunch allowance etc., all of which sum to an employee’s gross remuneration.

Non-Cash Compensations

This type of remuneration comes in various forms. Non-cash compensations are usually referred to as benefit-in-kind. It arises in instances where an employee is granted the use of the organisation’s asset; where a sale of the organization’s asset is made to the employee at a discounted price; where certain employee expenses are paid by the organisation etc. For instance, an employee can be said to have obtained a benefit-in-kind from his employer where the employee obtains a loan facility from the employer without interest or with lower-than-market interest rate. Another instance is where an employee is compensated by issuance of shares at no cost or at value lower than the market value of such shares. In both instances, the value of the benefit is the opportunity cost to the organisation for the loan facility granted or the share issued to the employee.

Employer Statutory Contributions as Non-Cash Compensation for Employee

An employer of labour is statutorily required to fulfil certain regulatory obligations such as pension contribution to its employees’ retirement savings accounts and obtaining group life insurance policy for its employees, in line with the Pension Reform Act 2014 (PRA). Employers are also required to contribute to the Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund based on the provisions of Employee Compensation Act 2010 and the National Health Insurance Scheme. These obligations create additional cost of employment to the organisation. Hence, they can be considered as a form of benefit-in-kind to the employee.

The PAYE Regulations of Personal Income Tax Act CAP P8 LFN 2004 (as amended) (“PITAM” or “the Act”) defines an employee’s emolument as total emoluments including all allowances, salaries, wages, perquisites, bonuses, and compensation of such employee. Perquisites can be defined as a benefit which is enjoyed or entitled to a person on account of such person’s job or position. The Black law dictionary defines perquisite as an emolument or incidental profits attached to an office or position beyond salary or regular fees.

Based on the foregoing, social security contributions as mentioned above made by an employer or organisation for the benefit of its employees should be considered as a benefit-in-kind to such employees. It is therefore arguable that such amounts expended by the employer should be included in the employee’s gross emolument for the purpose of computing the employee’s statutory reliefs as provided in PITAM. In addition, in line with the provisions of the PRA and PITAM, such contributions made by the employer for the benefit of its employees are tax-deductible in the hands of the employees.

Tax Implication of Cash & Non-Cash Compensations

Taxation of employee compensation is based on the provisions of the PITAM and it falls under the regulatory oversight of the respective State Internal Revenue Service depending on the state of residence of the employee. The value of non-cash compensation of the employee depends on the nature of the benefit. For instance, where an employee makes personal use of an asset that belongs to the employer, the annual value of benefit obtained from such use is 5% of the cost of such asset or 5% of market value where the cost cannot be ascertained. Furthermore, where the employer makes payment in the form or rent or lease for an asset which is to be used by the employee, the value of benefit-in-kind in this instance, is the total amount incurred by the employer for the provision of this benefit. However, necessary adjustments are made where any of these expenses is made good to the employer by the employee.

Based on the provisions of PITAM, considerations are given for non-taxable income, tax-deductible expenses, statutory reliefs and statutory deductions before the emolument is subjected to tax. Some non-taxable income as provided by the Act includes sum received as death gratuity or compensation for injuries and sum received as compensation for loss of office. It also includes interest on foreign currency domiciliary account and dividend, interest, rent, royalties, fee & commissions earned outside Nigeria and brought into Nigeria in foreign currency into a domiciliary account in a Nigerian Bank.

PITAM also treats certain expenses such as interest payments on mortgage for owner-occupied house incurred by the employee as tax-deductible, while social security contributions made to the national housing fund, national health insurance scgeme, national pension scheme and life assurance premium are treated as tax exempt. These allowances and exemptions are deducted from the employees’ gross emolument before the respective tax rates based on a graduated income scale are applied on the residual remuneration.

Conclusion

Employers face stiff penalties where they fail to perform their statutory obligations in relation to their employees. There is a need to ensure competence in the management of these functions so as to avoid additional cost resulting from payment of fines and penalties for not complying with the relevant statutes or not doing same with statutory timeframe. There is also a need for adequate tax planning in defining an organisation’s employee compensation structure in order to take advantage of the tax planning opportunities available in the respective tax laws.

Exposition by AndersenTax

PICTURES FROM THE INAUGURATION OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON CORPORATE COMMUNICATIONS & PUBLIC AFFAIRS

LAW REPORT REVIEW / LEGAL OPINION:

DISMISSAL MUST BE FOR JUSTIFIABLE REASON

Valentine Nkomadu vs. Zenith Bank Plc – unreported suit: NICN/206/2015

FACTS

The Claimant was the Branch Head of the Defendant’s Branch in Moloney Lagos. The defendant alleged that the claimant breached the bank’s credit policy which culminated in his indefinite suspension for 10 months without pay, and subsequent dismissal. Upon his dismissal, the Claimant instituted this action to seek redress.

CASE OF THE CLAIMANT

The Claimant argued that his dismissal was wrongful due to the bank’s failure to observe due process.

He further argued that he was not afforded any opportunity to defend himself over allegation bordering on misconduct which infringed on his right to fair hearing.

CASE FOR THE DEFENDANT

The defendant argued that the claimant’s dismissal was justified even though he was not given query or subjected to any disciplinary hearing, but only was summarily dismissed.

ISSUES FOR DETERMINATION

1. Whether the Defendant can dismiss the Claimant without justifiable reason.

2. Whether the dismissal of the Claimant can stand in the face of the Law.

JUDGMENT

The Court considered the arguments of both parties held that:

a) An employer is not at liberty to dismiss an employee without justifiable reason and observance of due process and fair hearing. The Court stated that the standard remains the same, whether in statutory employment or master/servant employment governed by common law.

b) The claimant’s summary dismissal without reason or due process emanated from the often confused interchange of dismissal and termination. Though, both are legally recognised exit pathways for an employee, they differ markedly in their operations and implications.

c) Termination is a contractual exit available to both employer and employee, and may go with or without reason, as it may not be for disciplinary purpose, but just for mere compliance with extant contract of service to bring the employment relationship to a lawful end.

d) Dismissal is solely a disciplinary measure available for only the employer with consequential denial of pecuniary entitlements of employee’s earned terminal benefits and image battering; casting doubt on future employability.

e) In any kind of employment regime (be it statutory or under common law), best practice is that dismissal must be for justifiable reason and due observance of extant contract of service and fair hearing.

f) An employer who decides to dismiss the employee is not only obliged to provide reason(s) for the dismissal but also justify the reason(s) if challenged. Thus, the often adopted veiled reason of ‘services no longer required’ or muted reason is not applicable to dismissal but limited to only termination, subject to service of appropriate notice period or salary in lieu of notice.

g) The act of dismissing an employee without a justifiable reason is not only in breach of the provision of the extant contract of service between the parties but also constitutes a flagrant breach of natural justice rule of fair hearing.

h) The court ordered the defendant to pay the claimant N13, 552.990.45 being his 10 months withheld pay.

i) The Court further ordered the bank to compute and pay the claimant’s terminal benefits having served for about 14 years, rising from the position of Executive Assistant II, to Senior Manager and pioneer Branch Head of the bank’s Moloney Branch, Lagos.

j) The court also awarded N2million in the claimant’s favour for the wrongful dismissal.

OPINION

It is important for employers of Labour to adhere strictly to standard Labour practice and rules to avoid unnecessary litigation and unwanted sanctions and penalties.

Furthermore, the reasoning of the court was that since dismissal has the adverse effect of taking away the employee’s earned terminal benefits, the employer is not at liberty to dismiss an employee without justifiable reason and observance of due process and fair hearing.

Recent Comments